Facial Nerve Paralysis

Facial nerve palsy is the most devastating neurological complication and therefore, an ENT surgeon tries to avoid the nerve injury during surgery. It has a negative impact on the patient’s quality of life, apart from the serious medicolegal issues for the operating surgeon. The term ‘Palsy’ incorporates both paralysis and paresis. ‘Paralysis’ refers to complete loss of muscle function, whereas ‘paresis’ is a partial paralysis or impaired muscle movement.

Facial nerve is the seventh cranial nerve emerging from pons (brainstem) and controls the muscles of facial expression. It is a mixed nerve having large motor fibres, a small sensory nerve (the nerve of Wrisberg- Nervus intermedius) and provides secretomotor fibres to the lacrimal gland and salivary glands. The number of myelinated axons ranges between 7000 and 9000 in the motor root of the facial nerve and between 3000 and 5000 in the nervus intermedius. Motor fibers brings signals and sensory nerves fibers carry signals to the central nervous system that is brain and spinal cord.

EMBRYOLOGY

Facial Nerve is an embryological derivative of the second branchial arch. The separation of the facial & internal acoustic nerves and development of the nervus intermedius (or nerve of Wrisberg) is completed by sixth week of gestation. The neural connections are developed by the 16th week. The bony facial canal develops until birth, enclosing the facial nerve in bone throughout its course except at the facial hiatus (the site of the geniculate ganglion) in the floor of the middle cranial fossa.

NUCLEUS OF VIIth NERVE

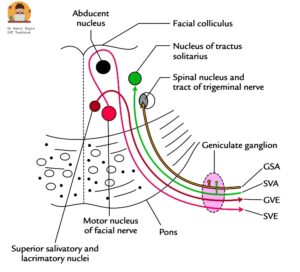

Cross section through the pons, superior view showing facial nucleus

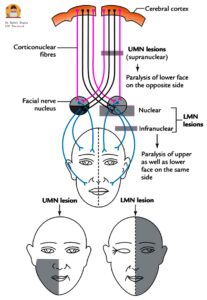

- Motor nucleus. Situated in the pons and receives fibres from the precentral gyrus. The supranuclear (upper) part of nucleus receives fibres from both the cerebral hemispheres and innervates forehead muscles, while the infra-nuclear part (lower) receives only crossed fibres from one hemisphere and supplies lower face. This explains why the function of forehead is preserved in supranuclear lesions because of bilateral innervation from both cerebral hemispheres. The emotional expressions of face like smiling and crying are preserved in supra-nuclear palsy due to thalamonuclear fibres supply to the facial nucleus.

- Nucleus solitarius. Situated in medulla oblongata and receives the taste fibres

- Superior salivatory nucleus. Situated in the pons and gives rise to parasympathetic fibres.

Diagram: Showing distribution of facial muscles paralysis following upper motor and lower motor facial nerve palsy

COMPONENTS OF FACIAL NERVE

There are four components of the facial nerve:

- General somatic/ sensory afferent (GSA) supplies cutaneous sensation, including pain from the posterosuperior aspect of external canal, concha and the tympanic membrane and terminate in the spinal nucleus of the trigeminal nerve. These fibres are responsible for cough reflex during wax removal, idiopathic otalgia, Hitzelberger’s sign and account for vesicular eruptions in Ramsay Hunt syndrome. It also brings proprioceptive sensation from the facial muscles.

- Special visceral/ sensory afferent (SVA) brings taste from the anterior two-thirds of tongue via chorda tympani and soft and hard palate via greater superficial petrosal nerve and terminate in the Nucleus tractus solitarius (gustatory nucleus) in the brainstem.

- General visceral/ motor efferent (GVE) supplies secretomotor fibres to lacrimal, submandibular and sublingual glands and the smaller secretory glands in the nasal mucosa and the palate. They are preganglionic parasympathetic fibres and originates from lacrimatory and superior salivatory nuclei in the brainstem

- Special visceral/ motor efferent (SVE) supplies all the muscles derived from the second branchial arch, i.e. all the muscles of facial expression, buccinator, stapedius, platysma, the posterior belly of digastric and stylohyoid.

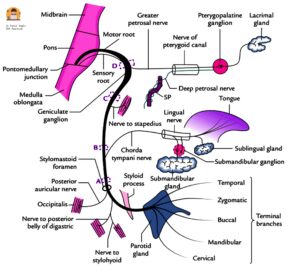

COURSE OF FACIAL NERVE.

The facial nerve follows a complex course which can be divided into three parts.

- Intracranial course. The facial nerve arises from the facial motor nucleus located in pons, hooks round the nucleus of VIth (abducens) nerve and are joined by the sensory root (nerve of Wrisberg), exits the brainstem at pontomedullary junction caudal to the fifth cranial (trigeminal) nerve and approximately 1.5 mm anterior, medial, and superior to the VIIIth cranial (vestibulocochlear) nerve and travels through posterior cranial fossa and enters the porus (medial end) of internal acoustic meatus. Length of this segment is 24 mm.

- Intratemporal course: The sensory and motor roots travel through theinternal acoustic meatus, enters the bony facial fallopian canal, traverses the narrow petrous temporal bone and exits from the stylomastoid foramen. The intra-temporal part is further sub-divide into four segments :

- Meatal segment – From porus (medial end) to fundus (lateral end) of internal acoustic meatus.i.e. it travels through internal meatus in the anterior-superior quadrant of the IAC along with vestibulocochlear nerve and internal auditory artery. Length of this segment is 8-10 mm.

- Labyrinthine segment – It starts from fundus of meatus to the geniculate ganglion where nerve takes a sharp ‘hairpin’ 750 degree turn posteriorly forming a first genu (anterior genu). Labyrinthine segment is the narrowest, hence most vulnerable to get compressed by oedema or inflammation leading to paralysis. In-addition, the segment is susceptible to low-flow state and vascular compression as it lacks anastomosing arterial cascades.

- Tympanic segment – It begins from the geniculate ganglion, courses posteroinferiorly to just above the pyramidal eminence. Facial nerve traverses medial to incus, runs posterior-superior to the cochleariform process ,above the oval window and below the lateral semi-circular canal. At the pyramidal process, the tympanic segment takes second turn inferiorly (at the second genu) to become the mastoid or vertical segment. Length of this segment is 8-11 mm. Due to the high incidence of fallopian canal dehiscence in tympanic segment, it is the most common site of injury during middle ear surgery.

- Mastoid or vertical segment – The tympanic segment takes second turn inferiorly (at the second genu located lateral and posterior to the pyramidal process) to become the mastoid or vertical segment. The nerve continues vertically down the anterior wall of the mastoid process to the stylomastoid foramen. The mastoid segment is the longest part(10-14mm) of the intratemporal course of the facial nerve. Second genu is the most common site of injury during mastoid surgery .

Diagram : Showing course and branches of facial nerve

3. Extracranial course. The nerve exits from stylomastoid foramen, travels anterior to the posterior belly of the digastric, lateral to the styloid process, enters the parotid gland high up on its posteromedial surface and divides within the gland, usually just behind and superficial to the retromandibular vein and external carotid artery (ECA). The length from stylomastoid foramen to initial intra-parotid bifurcation ranges between 8 -22 mm.

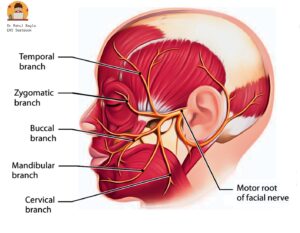

Diagram : Showing goose foot

It forms two divisions:

- Upper temporo-facial (further divided into temporal, zygomatic, upper buccal branch).

- Lower cervicofacial (further divided into lower buccal, mandibular and cervical branches).

Both divisions together form pes anserinus (goose-foot).

BRANCHES OF FACIAL NERVE

From geniculate ganglion

- Greater superficial petrosal nerve is the first branch of the facial nerve and carries secretomotor fibres to lacrimal gland and the glands of nasal mucosa and palate.

From mastoid segment

- Nerve to Stapedius arises at the level of second genu and supplies the stapedius muscle.

- Chorda tympani arises from the middle of vertical segment, 5-6 mm above the stylomastoid foramen and passes between the incus & neck of malleus and leaves the tympanic cavity via the petro-tympanic fissure. It brings taste sensation from anterior 2/3rd of tongue and supplies secretomotor fibres to submandibular and sublingual glands.

- Nerve from auricular branch of vagus.

At the stylomastoid foramen

- Posterior Auricular Nerve: After exiting the stylomastoid foramen, the facial nerve gives off a posterior auricular branch, which supplies auricular muscles (superior & posterior) and occipitalis muscle and communicates with auricular branch of vagus.

- Small Muscular Branches.

- Nerve to stylohyoid innervates the stylohyoid muscle (a suprahyoid muscle of the neck). It elevates the hyoid bone.

- Nerve to posterior belly of digastric. Innervates the posterior belly of the digastric muscle (a suprahyoid muscle of the neck). It elevates the hyoid bone.

Communicating Branch

It joins auricular branch ofvagus and supplies the concha, retro-auricular groove, posterior meatus and the outer surface of tympanic membrane.

Peripheral Branches to the face.

- It forms two divisions

- Upper temporofacial – Further divided into temporal, zygomatic branch.

- Lower cervicofacial – Further divided into buccal, mandibular and cervical branches.

VASCULAR SUPPLY OF FACIAL NERVE

The three main arteries supplying the facial nerve are:

- Labyrinthine artery, a branch of the anterior inferior cerebellar artery.

- Superior petrosal artery, a branch of the middle meningeal artery.

- Stylomastoid artery, a branch of the postauricular artery.

| Area | Blood supply |

| Cerebellopontine angle | Supplied by anterior-inferior cerebellar artery. |

| Intracranial, meatal and labyrinthine parts | Supplied by labyrinthine artery. |

| Geniculate ganglion and adjacent areas | Supplied by the superficial petrosal artery branch of the middle meningeal artery. |

| Tympanic and mastoid segments | Supplied by the facial arch, formed by the superficial petrosal branch of the middle meningeal artery and stylomastoid branch of posterior auricular artery. |

| Stylomastoid foramen to the parotid gland | The posterior auricular and occipital arteries and their branches, including the stylomastoid artery. |

| The temporofacial and cervicofacial branches | Supplied by collaterals of the superficial temporal, transverse facial, facial and maxillary arteries. |

Veins accompany the arteries in the fallopian canal. Lymphatic vessels are located in the epineurial layer.

SURGICAL LANDMARKS OF FACIAL NERVE

For middle ear and mastoid surgery

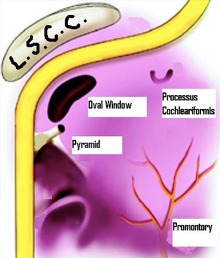

- Processus cochleariformis. It demarcates the geniculate ganglion which lies just anterior to it. Tympanic segment of the nerve starts at this level.

- Oval window and horizontal canal. The facial nerve runs above the oval window (stapes) and below the horizontal canal.

- Short process of incus. Facial nerve lies medial to the short process of incus at the level of aditus.

- Pyramid. Nerve runs behind the pyramid and the posterior tympanic sulcus.

- Tympanomastoid suture. In vertical or mastoid segment, nerve runs behind this suture.

- Digastric ridge. The nerve leaves the mastoid at the anterior end of digastric ridge.

Surgical landmarks of the facial nerve in middle ear and mastoid surgery.

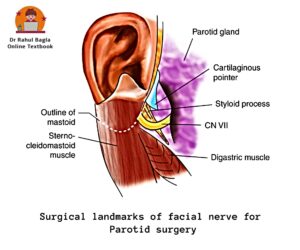

For parotid surgery

- Tragal pointer. The main trunk of nerve lies 1 cm medial and slightly antero-inferior to the pointer. Tragal pointer is a sharp triangular piece of pinna cartilage and it “points” to the nerve.

- Posterior belly of digastric. When retrograde dissection of this muscle is done along its upper border up to its attachment with the mastoid process, the facial nerve is seen passing between the mastoid and the styloid process.

- Tympano-mastoid suture. The trunk of the nerve can be identified 6–8mm below the inferior ‘drop off’ of the tympano-mastoid suture.

- Styloid process. The nerve passes laterally to the styloid process.

ANOMALIES OF FACIAL NERVE

Nerve anomalies are more common in congenitally malformed ears; hence the clinician should be careful while operating such ears.

- Bony dehiscence: The most common site of absence or dehiscence of bony cover is tympanic segment over the oval window . Other sites: near geniculate ganglion or in area of retrofacial mastoid cells. A dehiscent nerve is likely to be injured during surgery and infections of middle ear or mastoid.

- Prolapse of nerve: The dehiscent nerve may prolapse over the stapes creating difficulty in stapes surgery or ossicular reconstruction surgery.

- Hump: The nerve at times makes a hump posteriorly nearthe horizontal canal , hence vulnerable to injury while during mastoid surgery.

- Bifurcation and trifurcation. The vertical part offacial nerve bifurcates or trifurcates, each may occupy different canals and exiting through individual foramen.

- Bifurcation and enclosing the stapes. The nervebifurcates proximal to oval window—one of the branch passes above and the other below it and then both re-unite.

- Between oval and round windows. Just before ovalwindow the nerve crosses the middle ear between oval and round windows.

HISTOLOGY OF NERVE

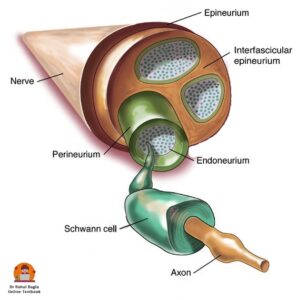

A peripheral nerve fibre is covered by three layers of connective tissue. Each nerve fiber is surrounded by endoneurium. A group of many fibres form fascicle bound together by another connective tissue called perineurium .There is an outermost layer of additional connective tissue surrounding many fascicles, called as epineurium. The three connective tissue layers maintain tensile strength, preventing its deterioration by cholesteatoma or vestibular schwannomas. The main glial cells of peripheral nervous system are schwann cells which provide trophic support to neurons.

Diagram: Showing cross section structure of nerve

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF NERVE INJURY

In 1941, Seddon introduced a classification of nerve fibre injury based on types of nerve fibre injury and continuity of the nerve.

- Neuropraxia is the least severe form of injury caused due to disruption to blood supply (ischaemia) or compression of the nerve. Release of the pressure results in a rapid and complete recovery of function (6-8 weeks). There is no residual dysfunction and wallerian degeneration does not occur.

- Axonotmesis is a more severe form of crush injuryor sectioning of an axon with disruption of the axoplasmic flow but with intact epineurium. All three connective tissue layers are preserved. Wallerian degeneration occurs distal to the site of injury over a period of 72-96 hours following injury. Regeneration occurs over weeks to days of injury.

- Neurotmesis is the most severe form of nerve injury caused due to severe contusion , stretch or laceration. There is complete loss of sensory, motor function. Treatment involves some form of surgical intervention .

Sir Sydney Sunderland in 1951 described axonotmesis of Seddon’s classification in a more detailed fashion and his classification is now widely accepted.

- 1° = Injury is reversible (as blockage to axoplasmic flow is partial) and full recovery is seen (Neurapraxia).

- 2° = Wallerian degeneration occurs. There is loss of axons with preserved endo-neural architecture. Recovery is good and usually complete (Axonotmesis).

- 3° = Disruption of endoneurium occurs. There is partial recovery, axons of one tube can grow into another. Synkinesis may occur (Neurotmesis).

- 4° = Disruption of perineurium in addition to above, only epineurium is intact. There is partial transection of nerve. Scarring will impair nerve regeneration of and poor recovery is seen.

- 5° = Disruption of epineurium in addition to above results in total disruption of nerve continuity (complete nerve transection); recovery requires surgical intervention.

1°, 2°,3° are seen in viral and inflammatory disorders while 4°and 5° are reported in surgical or accidental trauma and neoplasm.

EVALUATION OF FACIAL NERVE PALSY

- History. The diagnosis can be made on the basis of a thorough history, physical examination and diagnostic testing when required. The time of onset, duration and progression of the disease may indicate towards its aetiology and determine prognosis. The longer the duration of palsy, lesser the chances of spontaneous recovery. Recent H/o surgery, facial/ head trauma, ear complaints/ vertigo, headache must be taken. Concurrent medical conditions such as diabetes, pregnancy, autoimmune disorders and cancer should be noted.

- Bell’s palsy is mostly idiopathic, but following clinical presentations should raise a suspicion of an underlying neoplasm and needs to be investigated thoroughly.

- Progressive facial nerve palsy > 3 weeks

- Or an incomplete facial nerve palsy that does not start to recover after 3–6 weeks and

- Ipsilateral recurrent facial palsy.

- However, contralateral recurrence of facial nerve palsy is almost always benign.

- Physical examination. Full head, neck, otologic and cranial nerve examination. Signs of facial injury-laceration/ haematoma/ bruise. Attempt to localize exact site of lesion along the course of the facial nerve i.e. intracranial, intratemporal or extra-cranial.

- House-Brackmann grading system for facial palsy: Since the mid-1980s, the House-Brackmann system is widely used for grading of facial palsy. The degree of facial weakness should be recorded from the time of onset of facial palsy.

| Grade | Description | Characteristics |

| I | Normal | Normal facial function |

| II | Mild dysfunction | Slight weakness or synkinesis |

| III | Moderate dysfunction | Obvious asymmetry, but not disfiguring, synkinesis, contracture, or hemifacial spasm, complete closure with effort |

| IV | Moderately severe dysfunction | Obvious weakness or disfiguring asymmetry, normal symmetry and tone at rest, incomplete eye closure |

| V | Severe dysfunction | Barely perceptible motion, asymmetry at rest |

| VI | Total paralysis | No movement |

- Electrodiagnostic tests. These tests utilize electrical stimulation to assess nerve function and are most commonly used. The electrophysiological test is able to demonstrate degeneration as early as 3 days after onset. This information is useful to detect the degree of dysfunction, time to do surgical decompression of the nerve and also, predict prognosis.

- Minimal Nerve Excitability Test. It compares amount of transcutaneous current threshold required to elicit minimal muscle contraction on normal versus paralysed sides. The nerve isexcited by steadily increasing intensity till facial twitch is just noticeable. A difference of 3.5 m amp or more is significant and indicates poor recovery. No difference is seen between the normal and paralyzed side in conduction block. In other injuries, where degeneration sets in, nerve excitability is gradually lost. Degeneration of fibres is detectable > 48–72 h of its onset.

- Maximal Stimulation Test: The intensity of current level required to achieve maximum facial movement is recorded and compared with the normal side. Reduced or absent response even with maximal stimulation is suggestive of nerve degeneration and the recovery is usually incomplete. The above two tests are rarely used due to limitations in terms of accuracy, reproducibility, inter-observer variation and does not carry any prognostic value.

- Electroneuronography (ENoG ) is the objective measure of facial nerve integrity and carries prognostic value. ENoG is most useful between 4 and 21 days of the onset of complete paralysis and has no role in first 3 days. A supra-maximal stimulus is delivered to the facial nerve trunk at the stylomastoid foramen. The stimulation electrode is located at the stylomastoid foramen and the recording electrode is located near the nasolabial fold to pick up evoked biphasic compound muscle action potential (CMAP). The action potential of paralysed side is compared with the normal side (which serves as a control).

- If the CMAP amplitude on the affected side is 10% of the normal side, then 90% degeneration of axons has been sustained.

- Degeneration of >90% occurring in the first 14 days of complete paralysis has a poor recovery rate

- Faster rate of degeneration occurring < 14 days has a still poorer prognosis.

- Electromyography (EMG). Electroneuronography (ENoG) and electromyography (EMG) are now most commonly used by ENT surgeons in clinical practice. EMG records active motor unit potentials of the orbicularis oculi muscles during rest and voluntary contraction. Electromyography is useful in planning reanimation procedures in long-standing cases of facial paralysis. It measures:

- Fibrillation potentials (evidence of Wallerian degeneration appears 2-3 weeks after denervation).

- Polyphasic innervation potentials (early signs of re-innervation appear 6–12 weeks prior to clinical evidence of facial function)

- Presence of normal or polyphasic potentials after 1 year of injury suggests ongoing re-innervation and there is no need for reanimation procedure. Follow-up is advocated.

- Presence of fibrillation potentials indicate lower motor neuron denervation, but intact motor end plates. Surgical exploration is needed to maintain nerve continuity, either by end-to-end anastomosis, interposition grafting, re-routing or re-innervation techniques.

- Electrical silence means atrophy of motor end plates and fibrous replacement of muscle. There is need for muscle transfer or transposition procedures rather than nerve substitution.

ENoG and EMG tests provide information about the facial nerve distal to the stylomastoid foramen. These tests are required to prognosticate in cases of facial paralysis and in deciding the procedure for reanimation, i.e. nerve substitution versus muscle transposition or sling operation.

- Transcranial magnetic stimulation. is used to stimulate the facialnerve within the cranium in exactly the same way as conventional electrostimulation.

LOCALIZATION OF SITE OF LESION

A. Central facial paralysis. Function of forehead is preserved because of bilateral innervation of frontalis muscle from both cerebral hemispheres. There is paralysis of only the lower half of face on the contralateral side. The emotional expressions of face like smiling and crying are also preserved. Central facial paralysis is caused by brain abscess, Pontine gliomas, Poliomyelitis, Multiple sclerosis and cerebrovascular accidents (e.g. haemorrhage, embolism).

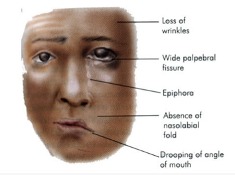

B. Peripheral facial paralysis. All the muscles of the face on the involved side are paralyzed. Patient is unable to frown, close the eye, purse the lips or whistle.

| Site of lesion | Signs |

| Level of nucleus | Associated paralysis of VIth nerve. |

| Cerebellopontine angle | Identified by the presence of vestibular and auditory defects and involvement of other cranial nerves such as Vth, IXth, Xth and XIth. |

| Bony fallopian canal, from IAC to stylomastoid foramen | Localized by topo-diagnostic tests given above. |

| Extra-temporal segment in parotid gland | Affects only the motor functions of nerve. It may sometimes be incomplete as some branches of the nerve may not be involved in tumour or trauma. |

Topognosis tests. Topographic diagnosis of facial nerve lesions refers to the functional testing of an individual facial nerve to pinpoint the site of injury.

| Test | Nerve branch assessed | Technique considerations | Assessment/ Outcome |

| Schirmer’s test | Greater (superficial) petrosal nerve | Eye is gently dried of excess tears or use Local anaesthetic drops. A Strip of filter paper is placed in the inferior conjunctival fornix of each eye for 5 minutes and patient is asked to close eyes. The length of paper moistened is compared between eyes | A reduction of 25% or a total of less than 25 mm is abnormal and indicates lesion proximal to the geniculate ganglion. |

| Stapedial reflex | Nerve to stapedius muscle | Can be tested by tympanometry. | Reflex is lost when lesion is above the nerve to stapedius. |

| Electrogustometry | Chorda tympani | The tongue is stimulated electrically to produce a metallic taste and the two sides are compared. Or a drop of salt or sugar solution placed on one side of the protruded tongue | Threshold of the test is compared between sides. Impairment of taste indicates lesion above the chorda tympani. |

| Salivary flow testing | Chorda tympani | Polythene tubes are placed into both Wharton ducts and salivary flow (no. of drops) is measured over a minute following a gustatory stimulus (6% citric acid on anterior part of tongue) | A reduction of 25% or more indicates lesion above the chorda. |

Topographical localization of the VIIth nerve lesions.

- Suprageniculate or transgeniculate lesion. Secretomotor fibres to the lacrimal gland leave at the geniculate ganglion and are interrupted in lesions situated at/or proximal to the geniculate ganglion.

- Suprastapedial lesions cause loss of stapedial reflex and taste but preserve lacrimation.

- Infrastapedial lesions cause loss of taste but preserve stapedial reflex and lacrimation.

- Infrachordal lesions cause loss of facial motor function alone.

CAUSES OF FACIAL PARALYSIS

The cause may be centralor peripheral. The peripheral lesion may involve the nerve in its intracranial, intratemporal or extratemporal parts. Peripheral lesions are more common and about two-thirds of them are of the idiopathic variety.

Table: Causes of facial nerve palsy

| Congenital facial palsy | Moulding of head during labour , Forceps delivery, cephalopelvic disproportion, Dystrophia myotonica, Moebius syndrome (bilateral facial nerve palsy often associated with unilateral or bilateral palsy of the abducens nerve ) | |

| Central | Brain abscess, Pontine gliomas, Poliomyelitis, Multiple sclerosis | |

| Intracranial part (cerebellopontine angle) | Acoustic neuroma, Meningioma, Congenital cholesteatoma, Metastatic carcinoma, Meningitis | |

| Intratemporal part | Idiopathic – Bell palsy, Melkersson syndrome, familial, Autoimmune syndrome, Temporal arteritis, Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, Polyarteritis nodosa, Landry–Guillain–Barré syndrome (ascending paralysis), Multiple sclerosis, Myasthenia gravis, multiple sclerosis, myasthenia gravis and sarcoidosis Infections – Acute suppurative otitis media, Chronic suppurative otitis media, Herpes zoster (Ramsay Hunt syndrome), Malignant otitis externa, Chicken pox, Encephalitis Poliomyelitis (type I) Mumps, Syphilis, Tuberculosis, Lyme disease, Infectious mononucleosis (glandular fever), Leprosy, Malaria, Botulism, Mucormycosis, encephalitis, polio. Trauma – Surgical: Mastoidectomy and stapedectomy. Accidental: Fractures of temporal bone, Basal skull fracture Neoplasms – Malignancies of external and middle ear, Glomus tumour, VIIth nerve tumour, Metastasis to temporal bone (from cancer of breast, bronchus, prostate), Jugular paraganglioma, Tympanic paraganglioma, Scleroma, Meningioma, Haemangioblastoma, Neurofibromatosis II. |

|

| Extracranial part | Malignancy of parotid, Accidental injury in parotid region, Neonatal facial injury (obstetrical forceps), Facial injuries, Penetrating injury to middle ear, Altitude paralysis (barotrauma), Scuba diving (barotrauma), Lightning | |

| Iatrogenic | Post-Immunization, Facial Or Dental Surgery Including Parotid Or Masseteric Surgery, Facelift Surgery, Tumour Resection, Resection Of Acoustic Neuromas, Embolization, Mandibular block anaesthesia | |

| Systemic | Diabetes Mellitus, Hypothyroidism, Uraemia, Polyarteritis Nodosa, Wegener’s Granulomatosis, Sarcoidosis, Leprosy, Leukaemia, Demyelinating Disease, Pregnancy, Hypertension, Acute Porphyria | |

| Toxic | Thalidomide Tetanus, Diphtheria, Carbon Monoxide, Ethylene Glycol, Alcohol, Arsenic, Carbon Monoxide, Misoprostol, Thalidomide, Anti-Tetanus Serum Vaccine for Rabies |

A. IDIOPATHIC

Bell’s Palsy is an idiopathic, acute onset peripheral facial palsy. The term idiopathic palsy is reserved for cases of facial palsy that have signs and symptoms consistent with the palsy and in which a diligent search for other causes yields negative results.

Minimum diagnostic criteria for labelling bell’s palsy.

- Paralysis or paresis of all muscle groups on one side of the face

- Sudden onset

- Absence of signs of central nervous system disease

- Absence of signs of ear or CPA disease

Incidence.

- 60 %- 75 % of facial palsy is Bell’s type

- Any age group may be affected though incidence rises with increasing age. A positive family history is present in 6–8% of patients.

- Recurrence is seen in 7 to 12% of patients; however, recurrence should heighten suspicion for another aetiology, such as a tumour involving the facial nerve.

- Risk of Bell’s palsy is high in diabetic patients (with microvascular angiopathy) and in pregnant women in 3rd trimester (retention of fluid leading to oedema or compression within Fallopian canal).

- Bell’s palsy is recurrent in 4.5–15% of patients

Diagram showing Facial paralysis of left side

Aetiology

1. Viral Infection. Although frequently called idiopathic facial paralysis, a viral aetiology is the most likely cause; numerous studies have identified herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), herpes sim- plex virus type 2 (HSV-2), varicella zoster virus (VZV), human herpesvirus, influenza B, adenovirus, Coxsackie virus and Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) as the causative agents.

2. Vascular Ischaemia. Primary ischaemiais induced by cold or emotional stress. Secondary ischaemia is an extension of primary ischaemia in which fluid exudation, oedema leads to compression of microcirculation of the nerve.

3. Hereditary. There may also be an inherited tendency toward developing Bell’s palsy.

4. Autoimmune Disorder: Changes in T-lymphocyte have been observed in cases of facial palsy.

Sign and symptoms.Abrupt in onset, and patient may notice the asymmetry when wake up in the morning or while drinking or eating.

- Patient is unable to open or close his eye on the affected side. If he attempts to close his eye, eyeball turns up and out (Bell’s phenomenon).

- Facial asymmetry.

- Epiphora.

- Drooling of saliva from the angle of mouth.

- Pain in the ear (otalgia) may precede or accompany the nerve paralysis.

- Some complain of noise intolerance (stapedial paralysis) or loss of taste (involvement of chorda tympani).

Diagnosis. It is usually clinical.

- Rule out all other known causes of peripheral facial paralysis.

- Nerve excitability tests. Can bedaily or on alternate days to monitor nerve degeneration.

- Topodiagnosis tests. To know the cause and the site of lesion.

Treatment

General management

Reassurance and psychological support.

- Relief of earache by analgesics.

- Eye care. Protection of the eye is the most urgent consideration in facial palsy. Due to incomplete closure of eye, tear film from the cornea evaporates causing dryness, exposure keratitis and corneal ulcer.

- Frequent use of eye drops (containing hydroxypropyl cellulose, hydroxypropyl methylcellulose or polyvinyl) frequently during the daytime, whilst at night, eye should be taped closed after putting thicker ointments containing petroleum, mineral oil or lanolin.

- Corneal protection with lubrication and patching.

- Use of large-lens sunglasses.

- Patients having long-term facial nerve palsy are advised to close their eye manually using a finger as well as attempting to stretch the upper lid in order to prevent shortening caused by unopposed action of levator palpebrae superioris muscle.

- Temporary tarsorrhaphy may also be indicated. Eye closure can also be improved by using gold-weight implant sutured to the tarsal plate deep to levator palpebrae muscle.

- Physiotherapy or massage of the facial muscles is encouraged.

Medical management

Steroids. Prednisolone is the drug of choice. If patient reports within 1 week, the adult dose of prednisolone is 1 mg/kg/day divided into morning and evening doses for 5 days. The patient is called for follow-up on the fifth day. If paralysis is incomplete or is recovering, dose is tapered during the next 5 days. If paralysis remains complete, the same dose is continued for another 10 days and thereafter tapered in next 5 days (total of 20 days). Steroids can be combined with acyclovir for Herpes zoster oticus or Bell’s palsy. The usual recommended oral regime is prednisone 1mg/kg/day for 10 days and oral acyclovir (400mg five times daily) for 10 days or valacyclovir (500 mg, three times a day).

Contraindications to use of steroids include pregnancy, diabetes, hypertension, peptic ulcer, pulmonary tuberculosis and glaucoma. Steroids have been found useful to prevent incidence of synkinesis, crocodile tears and to shorten the recovery time of facial paralysis.

Surgical Treatment.Facial nerve decompression of vertical and tympanic segments or whole of the fallopian canal. It improves the micro-circulation and relieve pressure of the nerve.

Prognosis.The degree of facial nerve damage determines the extent of recovery. Normalfacial function is usually recovered in 1-3 months in 2/3rd of patients.80- 90% of the patientsrecover fully. 10-15% may show residual muscle weakness due to nerve degeneration. Better prognosis is seen in incomplete Bell’s palsy and in those patients who start recovering within 3 weeks of onset

Recurrent facial palsy may not recover fully.

Poor prognosis is seen if paralysis is complete at onset, age >60 years and in patients with absent stapedius reflex ,postauricular pain,dry eye, abolished taste sensation.

2. Melkersson-Rosenthal Syndrome

It is also an idiopathic rare neurological disorder. Predominately in the second decade of life. It is characterised by a triad of relapsing and increasingly severe facial paralysis, swelling of lips ( cheilitis) and fissuring of the tongue.

Causes : Genetic factors, dietary factors/ allergens, associated with Crohn’s disease.

B. INFECTIONS

1. Otitis media. Facial nerve paralysis can occur as a complication in both acute and chronic otitis media.

- Acute otitis media. Inflammation of middle ear may cause direct infection through bony canal dehiscence. It is treated by systemic antibiotics.

- Chronic otitis media. Cholesteatoma or granulation tissue erode the bony canal by osteitis and inflammatory oedema leading to compression of the facial nerve. Treatment is urgent exploration of the middle ear and mastoid.

2. Malignant otitis externa.

It is an severely progressive necrotizing Pseudomonas infection of the ear canal. Infection may rapidly spread to entire temporal bone and jugular foramen causing involvement cranial nerves (IX, X, XI, and XII) and may lead to skull base osteomyelitis. It is usually seen in immunocompromised patients, particularly the elderly diabetics, and in patients on long steroid therapy or chemotherapy. Facial paralysis is commonly seen.

In an elderly diabetic patient with severe otalgia and granulation tissue in the external ear canal at its cartilaginous–bony junction is a cardinal sign of skull base osteomyelitis and should not be underestimated.

Spread

- Anteriorly, infection spreads to temporomandibular fossa.

- Posteriorly to the mastoid

- Medially into the middle ear and petrous bone.

Pathogenesis. The infective process produces exotoxins and enzymes like elastase which digests vessel wall.

Symptoms.

- Penetrating earache which is continuous and severe in nature.

- Ear discharge is initially mucopurulent and later becomes foul smelling purulent and blood tinged.

- Both CHL and SNHL can occur

- Facial paralysis.

- Headache

- Vertigo

Signs

- Granulation tissue seen protruding into the EAC from the bony-cartilaginous junction

- Sagging of posterior meatal wall.

- Tympanic membrane. May be normal.

- Pinna. Tenderness is present and doughy on palpation.

- Mastoid tenderness

- Multiple cranial nerves (IX, X, XI, XII) involvement is seen in late stages.

Investigations.

- Culture sensitivity by ear swab.

- CT scans help to evaluate the extent of bony involvement but MRI provides more details regarding soft-tissue disease and can also evaluate the patency of the dural sinuses if combined with magnetic resonance angiography,

- Gallium-67 bone scan helps in confirming the diagnosis and follow-up of the patient. It is taken up by monocytes and reticuloendothelial cells, and is indicative of soft tissue infection. It can be repeated every 3 weeks to monitor the disease and response to treatment.

Differential diagnosis

- Diffuse otitis externa. There is absence of excruciating pain and presence of granulations in the ear canal.

Treatment.

Long-term administration of parental antibiotics, in combination with daily extensive debridement of necrotic and granulation tissue and vigilant management of diabetes and other compromising medical conditions. Surgical management is currently not indicated, diagnostic biopsies can be done to rule out malignancy.

Anti-pseudomonas antibiotics should be given for minimum 2-3 months.

Antibiotics found effective are:

- Gentamicin combined with ticarcillin.

- Third-generation cephalosporins

- Quinolones (ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin and levofloxacin) are also effective and can be given orally.

- Ciprofloxacin (750mg orally twice per day) seems to be the antibiotic of choice for maintainence and prolonged treatment for a minimum of 3 months to 1 year may be required, to avoid relapse.

- In case there is resistance to ciprofloxacin, antipseudomonal β-lactam agents (ceftazidime, piperacillin, imipenem) with or without combination of aminoglycoside can also be used. Aspergillus infection if found need systemic antifungal treatment.

3. Herpes Zoster oticus (Ramsay–Hunt Syndrome)

It is an acute peripheral facial neuropathy associated with a typical erythematous vesicular rash of the skin of the ear canal, auricle or mucous membrane of oropharynx. It is caused by the re-activation of the latent Varicella Zoster virus in the geniculate ganglion. The syndrome is more common in old age>60 years.

Clinical features.

- Anaesthesia of face, giddiness and hearing impairment due to involvement of Vth and VIIIth nerves.

- Excruciating (severe) otalgia

- Vesicles in EAC on affected side Facial nerve palsy (LMN type)

- Tinnitus, vertigo and a sensorineural hearing loss

Complications

- Post herpetic neuralgia

- Eye damage (blurred vision) may occur

- Hearing loss & facial weakness may be permanent

Prognosis

- The prognosis for Ramsay Hunt is worse than idiopathic facial palsy. Persistent weakness is observed in 30–50% of patients and

- Only 10% recover completely after complete loss of function without treatment.

Prevention

Children are vaccinated against chickenpox, reduces their chances of getting infection

Treatment

- The recommended regime is prednisone 1mg/kg/day for 5 days then tapered for 10 days, and intravenous acyclovir (250 mg three times daily).The combination of steroids and acyclovir also seems to reduce otalgia, vertigo and post-herpetic neuralgia.

- Oral acyclovir 800mg 5 times a day for 7-10 day.

- Surgical decompression is not indicated.

4. Guillain–Barré syndrome(acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy) is a rare autoimmune disorder. The most prominent feature is ascending symmetrical muscular weaknessthat is typically seen 2–3 weeks after an upper respiratory infection. Facial nerve paralysis may develop and is often bilateral.. The intravenous immunoglobulin infusionis themost effective treatment.Steroids have been shown to have no beneficial effect and may even delay recovery. Treatment also involves respiratory support and passive physiotherapy

5. Epstein–Barr infection (infectious mononucleosis)is clinically characterized by generalized lymphadenopathy, fever and sore throat and may be associated with facial nerve palsy. The presence of at least 10% of atypical lymphocytes on peripheral tests and positive serology will confirm the diagnosis. Forty percent of the EBV-associated facial nerve palsy cases are bilateral.

C. CONGENITAL FACIAL PALSY is clinically defined as facial palsy of 7thcranial nerve present at birth and shortly thereafter. It results because of relatively superficial position of the extracranial facial nerve in infants. Congenital Facial palsy of developmental origin is associated with anomalies of pinna and EAC such as microtia and atresia. Acquired causes of facial palsy include perinatal trauma, intrapartum compression

D. BILATERAL CONCURRENT FACIAL PARALYSIS. It is associated with Guillain-Barré syndrome, sarcoidosis, sickle cell disease, acute leukaemia, bulbar palsy, leprosy, cerebral lymphoma, Lyme disease, rabies, infectious mononucleosis and Moebius syndrome.

E. RECURRENT FACIAL PALSY RECURRENT FACIAL PALSY is seen in Bell palsy (3–10% cases), Melkersson syndrome, diabetes, sarcoidosis and tumours. Recurrent palsy on the same side may be caused by a tumour in 30% of cases. In contrast to recurrent ipsilateral facial paralysis, contralateral recurrence is almost always benign.

F. INFLAMMATORY DISORDERS OF FACIAL NERVE.

- Sarcoidosisis an autoimmune systemic disease. It is characterized by non-caseating granulomata formation in the lungs and occurs in 3rd–4thdecade of life. Facial nerve palsy which can develop alone or with uveitis and parotitis as a part of Heerfordt’s disease (Triad of uveoparotid fever). Palsy is often bilateral, sudden and resolve spontaneously. Elevated angiotensin converting enzyme titre and hypercalcemia helps to confirm the diagnosis.

Treatment.Systemic corticosteroids.

- Lyme disease

- It is a vector-borne (spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi), multisystem inflammatory disease involving skin, nervous system, heart and joints.

- Transmitted to humans by the bite of ticks.

Clinical features:

- Acute facial nerve palsy, which is usually unilateral but can be bilateral especially in children, recovers within few weeks to months.

- Flu-like symptoms

- Erythema migrans.

Treatment. Doxycycline or amoxicillin for 14–21 days in patients having facial nerve palsy. Doxycycline is contraindicated in patients below 8 years and in pregnant women.

G. TRAUMATIC FACIAL PARALYSIS

1. Fractures of Temporal Bone

Temporal bone is very thick and hard structure located in the base of the skull. Skull base has multiple foramina, increasing susceptiblity to traumatic injury. Temporal bone contains important structures like facial nerve, labyrinth, CN VIII, ossicles, carotid artery, jugular vein etc. Any or all structures can get involve in fractures of temporal bone.

Aetiology.

- Motor vehicle accident

- Fall from height

- Physical assaults

- Gunshot wound

- Any trauma causing head, maxillofacial and spine injuries.

Types of fractures.

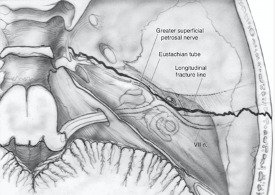

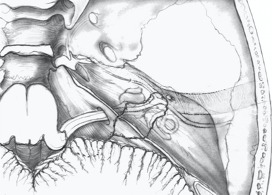

Its depends on the direction of fracture with respect to the long axis of petrous temporal bone

- Longitudinal.Runs parallel to long axis of petrous temporal bone. Starts at squamous part of temporal bone to end at foramen lacerum

- Transverse.Runs perpendicular to the petrous temporal bone. Starts at foramen magnum or jugular foramen towards the foramen spinosum

- Mixed (oblique). Having one or more features of both above fractures.

A longitudinal fracture runs along the axis of petrous pyramid. Typically, it starts at the squamous part of temporal bone, runs through the roof of the external ear canal and middle ear towards the petrous apex and to the foramen lacerum.

Transverse fracture. It runs across the axis of petrous. Typically, it begins at the foramen magnum, passes through occipital bone, jugular fossa and petrous pyramid, ending in the middle cranial fossa. It may pass me-dial, lateral or through the labyrinth.

Further complications that should be considered are CSF leak, meningitis, meningocoele from tegmen involvement, and vascular injury to the carotid canal or jugular fossa. Delayed complications can include labyrinthine ossificans and post-traumatic cholesteatoma.

Cause of facial nerve paralysis

- Oedema.

- Stretching

- Intraneural hemorrhage.

- Compression by a bony spicule.

- Dehiscence of nerve.

- Transection of nerve.

Investigations.

High-definition CT

- Type and direction of fracture

- Involvement of otic capsule

- Any associated complications.

Treatment of facial nerve paralysis

It depends upon time of onset of facial palsy following injury.

- Delayed onset paralysis. Treatment is same as Bell palsy and palsy almost always recovers.

- Immediate onset paralysis. Require urgent exploration.

- Facial nerve decompression

- Re-Anastomosis Of Cut Ends

- Cable Nerve Graft.

| Longitudinal | Transverse | |

| Incidence | Seen in 80% cases | Seen in 20% cases, but more common in children |

| Type of injury | Parietal blow, lateral blow over mastoid region | Occipital or frontal blow |

| Fracture line | Runs parallel to long axis of petrous temporal bone.Starts at squamous part of temporal bone toend at foramen lacerum | Runs perpendicular to the petrous temporal bone. Starts from foramen magum or jugular foramen towards the foramen spinosum |

| Injury to external and middle ear | present | Absent |

| Bleeding from ear | Common, due to injury to tegmen andtympanic membrane | Absent because tympanic membrane is intact. |

| Haemotympanum | Absent | Haemotympanum may be seen |

| Cerebrospinal fluid otorrhoea | Present, often mixed with blood and usually it is temporary. | Absent or unmanifested |

| Structures injured | Tympanic membrane , ossicles and tegmen | Labyrinth or CN VIII |

| Type of Hearing loss | Conductive, SNHL can also occur due to concussion but is not common. | Sensorineural |

| Vertigo | Less often; due to concussion | Severe, due to injury to labyrinth or CN VIII |

| Incidence of Facial paralysis | Seen in 20% cases, delayed onset. | Seen in 50% cases. Immediate onset. |

| Site of injury | Nerve is injured in tympanic segment, distal to geniculate ganglion | Injury to nerve in meatal or labyrinthine segment proximal to geniculate ganglion. |

| Skull base foramen | Ovale | Spinosum, lacerum |

- Iatrogenic Injury

- Ear or Mastoid Surgery

Facial nerve can get injured during middle ear or mastoid surgery. The most common site of injury during middle ear or mastoid surgery is the distal tympanic segment including the second genu, followed by the mastoid segment. The incidence of facial nerve palsy has been reported to be between 0.6% and 3.6%.

Treatment.

- Facial nerve injury recognized during surgery, exploration with decompression of proximal and distal segments of the nerve should be undertaken.

- Facial palsy in seen immediately after surgery and if the nerve was identified or was not at risk during the operation, a few hours of observation will usually allow for any local anaesthetic-induced weakness to clear. The possibility of a tight mastoid dressing over an exposed nerve should also be considered and it is wise to remove the pack. If the paralysis is incomplete, the patient should be started on oral steroids and observed clinically. In cases of progression to full paralysis, exploration should be considered.

- In rare cases, a delayed palsy is observed a few days after uneventful middle ear surgery. The aetiology is unclear, although reactivation of HSV or VZV is postulated as the underlying mechanism. Combined use of prednisone and acyclovir should be considered and the overall prognosis appears to be good.

Operative injuries to facial nerve can be avoided if attention is paid to the following:

- Knowledge of the course of facial nerve.

- Identification of surgical landmarks of the facial nerve.

- Chances of variations and anomalies of the facial nerve.

- Always work along the course of nerve and never across it.

- Use diamond burr while working close to nerve.

- Ensure constant irrigation while drilling in order to avoid thermal injury.

- Gently handle the nerve if it is exposed. Avoid any pressure of instruments on the nerve.

- Granulation tissue penetrating the nerve should not be removed.

- Always work using operating microscope under magnification

- Use intraoperative facial nerve monitor if available.

2. Parotid Surgery

Facial nerve can get injured in parotid surgery or sometimes it is deliberately excised in malignant tumours. Use of facial nerve monitor during parotid surgery helps in avoiding injury to facial nerve and at the end of the surgery the main trunk should be stimulated to confirm continuity.

3. Facial Nerve trauma

Surgical exploration and repair is advisable within 3 days if the patient is both medically and neurologically stable. Nerve stimulator is used to identify the distal segments of facial nerve branches.

4. Gunshot injuries

Facial nerve injury is seen in about 50%, and vertical segment being the mostcommonly affected.

Treatment. Urgent surgical exploration is required, as delay makes the nerve difficult to identify due to formation of granulation tissue. Reanimation surgeries like interval cable grafting is done if a segment of the nerve has been destroyed. Open mastoidectomy with a meatoplasty (to remove fragments of skin and bullet) should be done as there is a high risk of infection due to bony damage and subsequent cholesteatoma formation.

H. NEOPLASMS

1. Intratemporal Neoplasms

- Facial nerve schwannomas. It is a benign, slow growing tumour which occurs anywhere along the course of the facial nerve from the cerebellopontine angle to the branching of nerve in the parotid gland.It arises from Schwann cells within the nerve sheath.The presenting symptoms can be progressive or sudden onset or recurrent facial weakness and usually depends on the segment involved.MRI with gadolinium is mainstay for diagnosis and will show an enhancing (usually fusiform) lesion at the site of involvement.Management options are:

- Observation with serial scanning.

- Radiotherapy (stereotactic or fractionated).

- Surgery.Excision and nerve grafting and is usually reserved for tumours that have failed radiation treatment.

- Almost all intratemporal Neoplasms results in facial paralysis.

2. Tumours of Parotid

Facial paralysis is seen parotid gland tumours. Presence of facial palsy is mostly seen malignant tumours.

I. SYSTEMIC DISEASES AND FACIAL PARALYSIS

Sometimes peripheral facial paralysis is seen systemic diseases. Exclude Diabetes Mellitus, Hypothyroidism, Uraemia, Polyarteritis Nodosa, Wegener’s Granulomatosis, Sarcoidosis, Leprosy, Leukaemia, Demyelinating Disease, Pregnancy, Hypertension Acute Porphyria.

SEQUELAE/ COMPLICATIONS OF FACIAL PARALYSIS

Peripheral facial paralysis due to any cause may result in any of the following complications:

1. Incomplete Recovery. Facial asymmetry completely not resolved.It results in persistent tears in affected eye due to incomplete eye closure, difficulty in speaking clearly, involuntary drooling of saliva and difficulty in drinking and eating leading to psychological and social stigma.

2. Exposure Keratitis. Due to incomplete closure of eye, tear film from the cornea evaporates causing dryness, foreign body sensation, blurring of vision, exposure keratitis and corneal ulcer.

Treatment.

- Frequent use of eye drops (containing hydroxypropyl cellulose, hydroxypropyl methylcellulose or polyvinyl) frequently during the daytime, whilst at night, eye should be taped closed after putting thicker ointments containing petroleum, mineral oil or lanolin.

- Corneal protection with lubrication and patching.

- Use of large-lens sunglasses.

- Patients having long-term facial nerve palsy are advised to close their eye manually using a finger as well as attempting to stretch the upper lid in order to prevent shortening caused by unopposed action of levator palpebrae superioris muscle.

- Temporary tarsorrhaphy may also be indicated. Eye closure can also be improved by using gold-weight implant sutured to the tarsal plate deep to levator palpebrae muscle.

3. Crocodile tears (Gustatory Lacrimation). During recovery from facial nerve paralysis, the regenerating parasympathetic fibres of the salivary gland undergo synkinesis and misdirectly starts supplying the lacrimal gland instead of supplying the salivary glands. Therefore while eating food, instead of developing salivation, patient develops paroxysmal ipsilateral shedding of tears (lacrimation). Treatment is sectioning of greater superficial petrosal nerve or tympanic neurectomy.

4. Frey’s Syndrome (Gustatory Sweating). It occurs following parotid or neck dissection surgery. The overlying sweat glands gets aberrant reinnervation from postganglionic parasympathetic neurons resulting in flushing and sweating over the parotid area, instead of salivation during mastication.

5. Synkinesis (Simultaneous movement). It occurs due to abnormal regeneration of facial nerve fibers, which cross innervate to another nerve group of fibres, causing unwanted facial movement. It usually occurs following surgery or surgical repair of facial nerve. Patient may experience eye closure during a smile and laugh or while closing the eye, there is twitching of the corner of mouth. Treatment options are physical therapy, botulinum toxin, surgery.

6. Tics and Spasms. These are involuntary twitching of the eye and facial muscles on one side of the face, occurs as a result of faulty regeneration of fibres. It usually seen in childhood.

7. Contractures. Due to prolonged facial palsy, the facial muscles gets contracted and become atrophic. Shortening of the facial muscles affects the movements of face. Usually no facial asymmetry is visible during rest position. But sometimes the affected side of the face may appear slightly lifted and eye may appear smaller as compared to the other eye.

——————– End of the chapter ——————–

Learning resources.

- Scott-Brown, Textbook of Otorhinolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery.

- Glasscock-Shambaugh, Textbook of Surgery of the Ear.

- Logan Turner, Textbook of Diseases of The Nose, Throat and Ear Head And Neck Surgery.

- Rob and smith, Textbook of Operative surgery.

- P L Dhingra, Textbook of Diseases of Ear, Nose and Throat.

- Hazarika P, Textbook of Ear Nose Throat And Head Neck Surgery Clinical Practical.

- Mohan Bansal, Textbook of Diseases of Ear, Nose and Throat Head and Neck surgery.

- Anirban Biswas, Textbook of Clinical Audio-vestibulometry.

- W. Arnold, U. Ganzer, Textbook of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery.

- Salah Mansour, Textbook of Comprehensive and Clinical Anatomy of the Middle Ear.

- Susan Standring, Gray’s Anatomy.

- Ganong’s Review of Medical Physiology.

Author:

Dr. Rahul Kumar Bagla

MS & Fellow Rhinoplasty & Facial Plastic Surgery.

Associate Professor & Head

GIMS, Greater Noida, India

msrahulbagla@gmail.com