Juvenile Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma

Juvenile Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma is the most common benign tumour of the nasopharynx, almost exclusively affecting adolescent males, typically around 14 years (range 7–19 years). Although benign, it is highly aggressive and spreads to nearby structures through natural openings like foramina and fissures.

Aetiology

The exact cause is unknown, but hormone receptors (androgen, estrogen, progesterone) have been found in the tumour. Two main theories explain its origin:

- Testosterone Dependency Theory: This theory is supported by the tumour’s occurrence in adolescent males during puberty. The presence of male sex hormones, particularly testosterone, is believed to activate a pre-existing vascular hamartomatous nidus in the nasopharynx, causing it to grow into a full-fledged tumour. Therefore, hormonal factors play a significant role in its development.

- Branchial Arch Artery Theory: This theory suggests that JNA arises from the incomplete regression of the first branchial arch artery (maxillary artery), particularly in the region of the sphenopalatine foramen during embryonic development. This failure leaves behind a vascular remnant, a hamartomatous nidus, which later receives blood supply from the sphenopalatine and maxillary arteries and is stimulated by androgens at puberty. This theory explains the tumour’s typical location and its primary blood supply.

A primary aberration of the pituitary-gonadal axis is suggested but not proved.

Angiofibromas: Composition and Surgical Considerations

Angiofibromas are vascular malformations that are firm, non-encapsulated, highly fibrovascular tumours made of fibrous + vascular tissue. There is no true capsule; instead, the epithelial lining may thicken to form a pseudo-capsule.

- Components: Angiomatous (vascular) part – more in younger patients. Fibrous part – increases with age.

- Blood vessel structure: The tumour’s blood vessels lack a muscular layer, so they are incapable of contracting, which makes them prone to severe bleeding during surgical dissection

- Surgical challenge: Prone to severe bleeding during surgery. Bleeding cannot be controlled with adrenaline. The best approach is to dissect along the pseudo-capsule to minimise bleeding.

Site of origin and growth

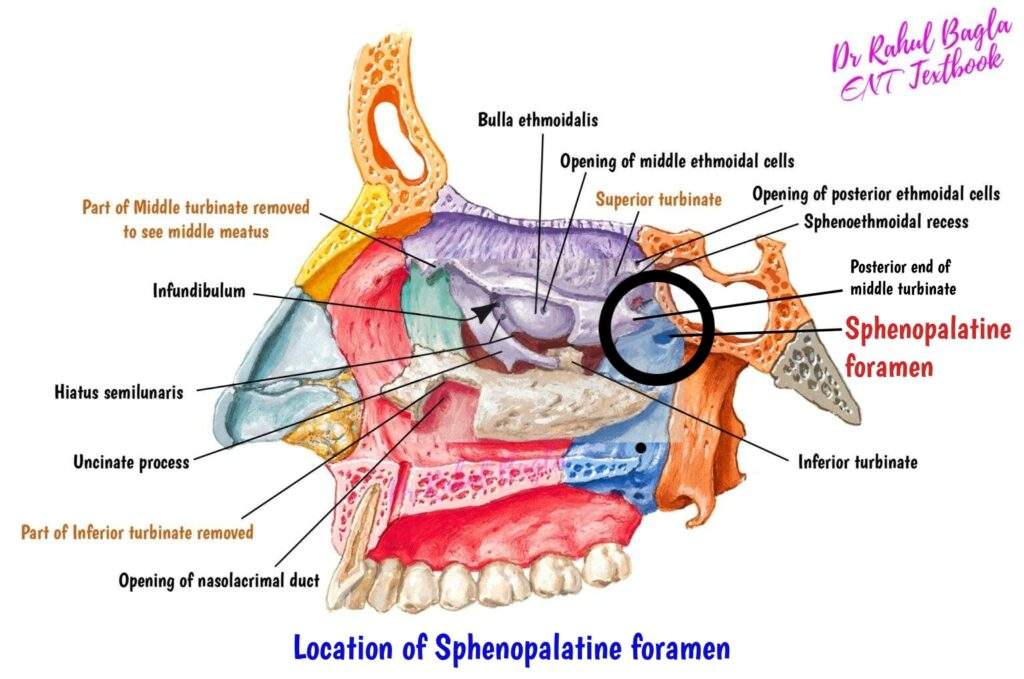

JNA is believed to originate from the posterior part of the lateral wall of the nasal cavity, from the superior margin of the sphenopalatine foramen and the vidian canal. The sphenopalatine foramen is present 1 cm behind the posterior end of the middle turbinate. From this starting point, the tumour grows aggressively into the nasopharynx, which is why it is often called a “nasopharyngeal angiofibroma.”

Relevant anatomy of the Sphenopalatine foramen

The sphenopalatine foramen is a key anatomical structure in the lateral wall of the nasal cavity, acting as a communication pathway between the pterygopalatine fossa and the nasal cavity. It’s situated in the posterolateral wall of the nasal cavity and is clinically significant because it’s the most common site of origin for Juvenile Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma (JNA). Several important neurovascular structures pass through the sphenopalatine foramen to supply the nasal cavity and nasopharynx. These include:

- Sphenopalatine artery: This is a terminal branch of the internal maxillary artery and is the main artery of the nasal cavity.

- Posterior superior and inferior nasal nerves: These branches of the maxillary nerve (V2) supply sensory innervation to the nasal cavity and nasopharynx.

- Sphenopalatine ganglion: This parasympathetic ganglion is also known as the Meckel’s ganglion. It sends secretomotor fibres to the nasal and palatine glands.

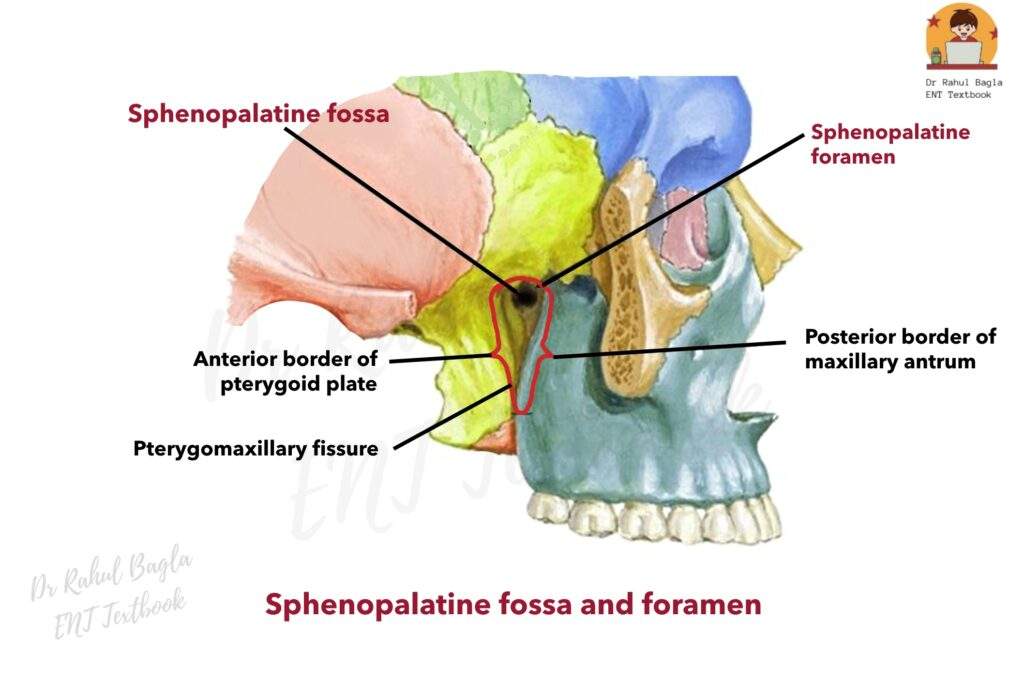

Sphenopalatine Fossa Boundaries

- Anteriorly: The posterior wall of the maxillary antrum (or maxillary sinus) forms the anterior boundary.

- Posteriorly: The anterior surface of the pterygoid plate defines the posterior boundary.

- Laterally: The infratemporal fossa lies lateral to this region.

- Medially: The lateral wall of the nasopharynx constitutes the medial boundary.

This fossa serves as a crucial anatomical crossroads, housing the sphenopalatine ganglion, branches of the maxillary nerve, and the terminal branches of the maxillary artery. Its location and connections are highly relevant in conditions like Juvenile Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma.

Blood Supply of Nasopharyngeal Fibroma

- External carotid artery (majority) – Internal maxillary artery, ascending pharyngeal artery, palatine arteries

- Internal carotid artery (less common), usually in larger tumours – Sphenoidal branches, ophthalmic artery.

Blood Supply of Nasopharyngeal Fibroma according to the site of the extension

- Nasopharyngeal fibromas receive their blood supply primarily from the internal maxillary artery and its branches, including the sphenopalatine and pterygovaginal arteries. These vessels provide blood to the tumour at its origin in the anterior nasopharynx and posterior nasal cavity.

- As the tumour grows larger and extends into areas such as the sphenoid sinus, infratemporal fossa, or parapharyngeal space, it acquires additional blood supply from other branches of the ECA, such as the accessory meningeal, ascending pharyngeal, and ascending palatine arteries.

- In advanced stages, the tumour’s blood supply becomes more complex, with contributions from the internal carotid arteries (ICAs) and, in some cases, the vertebral arteries. This bilateral blood supply is a characteristic of more advanced tumours, especially large juvenile angiofibromas.

Spread of Nasopharyngeal Fibroma

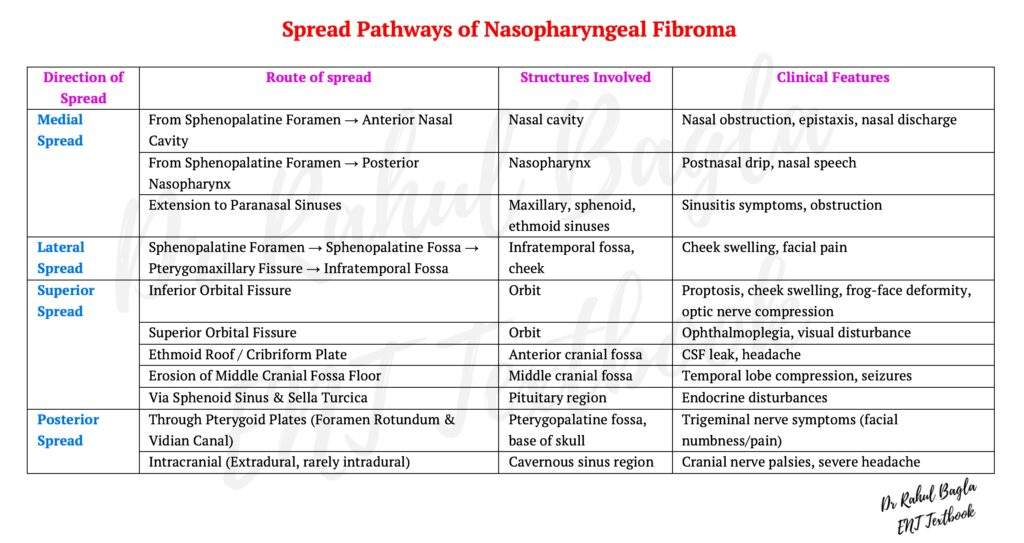

Nasopharyngeal fibroma, while benign, is a locally invasive tumour that tends to spread through anatomical spaces and foraminae, destroying adjoining structures. The tumour may extend into various areas, resulting in distinct symptoms and complications:

Medial spread from the sphenopalatine foramen

- Anteriorly into the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses: When the tumour extends into the nasal cavity, it can cause nasal obstruction, epistaxis (nosebleeds), and nasal discharge. From there, the tumour can invade the maxillary, sphenoid, and ethmoid sinuses, contributing to further complications and obstruction.

- Posteriorly into the nasopharynx.

Lateral spread from the sphenopalatine foramen

- Laterally into the sphenopalatine and Infratemporal Fossae: The tumour may spread laterally through the sphenopalatine foramen into the sphenopalatine fossa, and from there through the pterygomaxillary fissure into the infratemporal fossa and cheek. When the tumour is in the infratemporal fossa, it causes anterior bowing of the posterior wall of the maxillary sinus (antral sign or Holman-Miller sign seen on radiology) is pathognomonic of angiofibroma. From the infratemporal fossa, it can erode the greater wing of the sphenoid to reach the middle cranial fossa.

Superior spread from the sphenopalatine foramen

- Orbit: The tumour can reach the orbit via the inferior orbital fissure, leading to proptosis (bulging of the eye) and/or optic nerve compression, which can cause visual disturbances. And then through the superior orbital fissure, it enters the middle cranial fossa.

- Superiorly into the cranial Cavity: The tumour can extend into the cranial cavity in several ways:

– Anterior Cranial Fossa: Through the roof of the ethmoids or the cribriform plate.

– Middle Cranial Fossa: By eroding the floor of the middle cranial fossa or indirectly by invading the sphenoid sinus and sella turcica. In the former case, the tumour lies lateral to the internal carotid artery; in the latter case, medial to the artery.

Posterior spread from the sphenopalatine foramen

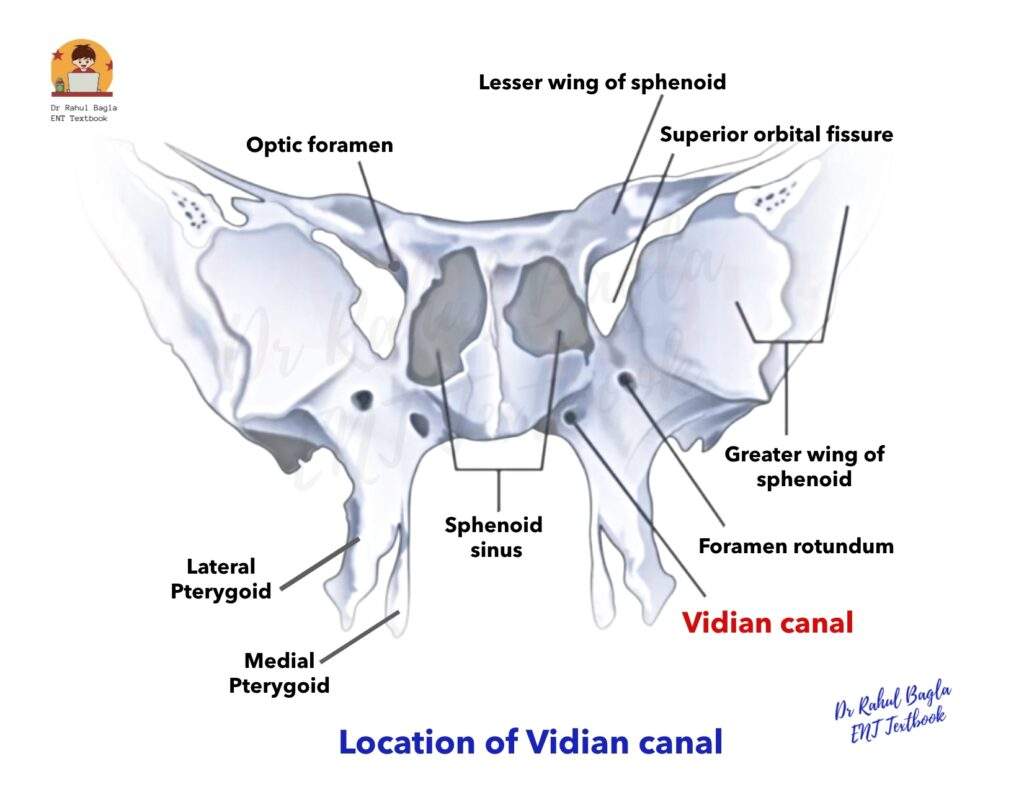

- Through the pterygoid plates. The spread will be through natural openings in the pterygoid plates (foramen rotundum and vidian canal). The maxillary nerve comes from the brain into the sphenopalatine fossa.

In cases of intracranial tumour growth, juvenile angiofibromas are primarily located in the extradural space. Dural infiltration or brain involvement is rare but can occur.

Clinical Features

The patient usually presents with nasal obstruction (80%) but also epistaxis (50%), headache (25%) and facial swelling (15%). He can also have eye symptoms and signs (diplopia, proptosis) and unilateral otological symptoms (OME).

- Age and Sex: This tumour predominantly affects males aged 10-20 years. It is rarely seen in older persons and females.

- Epistaxis: Profuse, recurrent, and spontaneous nasal bleeding are the most common symptoms. Patients often become markedly anaemic due to repeated blood loss.

- Nasal Obstruction and Speech Changes: Progressive nasal obstruction caused by the tumour mass in the postnasal space leads to hyponasal speech. There can be snoring and features of obstructive sleep apnoea.

- Hearing Loss and Otitis Media: Conductive hearing loss and otitis media with effusion occur due to the obstruction of the eustachian tube by the tumour.

- Nasopharyngeal Mass: The tumour appears as a sessile, lobulated, or smooth mass in the nasopharynx, obstructing one or both choanae. It is pink or purplish and has a firm consistency. Digital palpation should be avoided until the time of the operation.

- Frog facies. Long-standing tumours may present with proptosis, swelling of the cheek, and broadening of the nose.

- Trismus: May be seen in long-standing tumour in the infratemporal fossa.

- Other Clinical Features: There may be involvement of the second, third, fourth, and sixth cranial nerves.

Diagnosis and Investigations of Nasopharyngeal Fibroma

The diagnosis of nasopharyngeal fibroma is primarily based on its typical clinical and radiological findings. Biopsy of the tumour is generally avoided due to the high risk of severe bleeding. If a biopsy is necessary to differentiate it from other tumours, it should be performed under general anaesthesia with all arrangements in place to control bleeding and provide blood transfusions if needed.

1. Nasal Endoscopy: This procedure reveals a sessile, lobulated, or smooth reddish mass in the nasal cavity.

2. Contrast-Enhanced Computed Tomography (CT) Scan Nose & PNS: It is the investigation of choice, and it is essential for staging the tumour, which guides treatment planning. It has replaced the traditional X-rays. After a patient is injected with a contrast dye, the tumour shows up as a bright, enhanced mass. This helps the scan reveal its size, spread, and whether it has destroyed or displaced surrounding bones.

The tumour causes several key signs on the scan:

- Anterior bowing of the posterior wall of the maxillary sinus (also known as the antral sign or Holman-Miller sign) is a definite indicator of an angiofibroma.

- Posterior bowing of the pterygoid plates and erosion of the sphenoid sinus can be seen.

- The scan will also show a widening of the pterygomaxillary fissure, vidian canal, pterygopalatine fossa, and sphenopalatine foramen.

- The widening of the pterygoid wedge is called Ramaharan’s sign.

During surgery, the surgeon drills the base of the pterygoid to remove all parts of the tumour and reduces the rate of recurrence of JNA. A post-surgery CT scan will then reveal the “chopstick sign,” which is caused by the separation of the two pterygoid plates, resulting in parallel lines.

Radkowski Classification of Juvenile Angiofibroma.

| Stage | Description | Direction of spread |

|---|---|---|

| 1a | Tumour limited to nasal cavity & nasopharynx | Medial |

| 1b | Tumour extends to one or more paranasal sinuses from nasal cavity. | Medial |

| 2a | Minimal extension into pterygopalatine (sphenopalatine) fossa | Lateral |

| 2b | Complete occupation of pterygopalatine fossa ± orbital involvement | Lateral |

| 2c | Extension into infratemporal fossa ± cheek or pterygoid plate involvement | Lateral |

| 3a | Minimal intracranial extension (skull base erosion, middle cranial fossa, or pterygoids) | Intracranial |

| 3b | Extensive intracranial extension ± cavernous sinus involvement | Intracranial |

3. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): MRI is superior for defining orbital and intracranial soft tissue extensions. An MRI is recommended in tumours with suspected intracranial extension, cavernous sinus involvement, orbital extension and carotid involvement. On a specific type of MRI scan called a T2 image, the tumour can have a “salt-and-pepper” appearance. This happens because:

- The fibrous parts of the tumour look white (salt).

- The blood vessels within the tumour show up as dark spots (pepper).

While this “salt-and-pepper” pattern is typically associated with another type of tumour called paragangliomas on T1 scans, it is more commonly seen in juvenile angiofibroma on T2 scans.

4. Carotid Angiography: Carotid Angiography is now standard for angiofibroma cases, particularly when embolisation is planned before surgery. The main arteries targeted for embolisation are the maxillary and ascending pharyngeal arteries.

What it shows:

- The size and spread of the tumour.

- How vascular the tumour is (how many blood vessels it has).

- The feeding blood vessels that feed the tumour usually come from the external carotid artery system.

Embolisation is the process of blocking the tumour’s blood supply. It is done 24-48 hours before surgery to reduce bleeding during the operation. Surgery must be performed within this 24-48-hour window to prevent revascularisation from the contralateral side. Using embolisation has significantly reduced blood loss during surgery. In the past, the average blood loss was about 2000 mL, but now it is less than 1000 mL. While angiography is used to identify and embolize the feeding vessels, some surgeons prefer to tie off these vessels during the actual surgery. This approach helps them avoid the risks associated with embolisation and allows them to spot any remaining tumour tissue by observing where bleeding occurs.

Treatment of Juvenile Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma. Surgical excision is the treatment of choice, though radiotherapy and chemotherapy singly or in combination have also been used.

Surgery

Surgical excision is the primary treatment of choice for juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Spontaneous regression of the tumour does not occur, and no wait-and-watch policy should be adopted. Various surgical approaches have been described:

- Nasal endoscopy approach.

- Trans palatal approaches: Transpalatal approach or Transpalatal with sublabial extension (Sardana’s approach)

- Trans maxillary approaches: Lateral rhinotomy/medial maxillectomy or Midfacial degloving or Le-Fort I osteotomy approach or Maxillary swing/facial translocation approach, or Wei’s operation

- Lateral skull base approaches: Preauricular subtemporal infra-temporal approach or Infratemporal approach type C.

- Combination of approaches.

The specific approach depends on the tumour size, extension, surgeon experience and familiarity with the approach. Endoscopic resection has become the preferred technique for most juvenile angiofibromas in the hands of experienced surgeons specialising in sinonasal care. Before surgery for JNA, 2–3 units of cross-matched blood should be reserved, as bleeding can still occur despite embolisation. Blood loss can be reduced by head elevation, hypotensive anaesthesia, and modern instruments like LASER, coblation, or harmonic scalpel. The surgeon first frees all extensions, ligates the maxillary artery, and then removes the tumour. Finally, drilling the vidian canal and pterygoid base helps prevent recurrence.

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy has been used as a primary treatment or for recurrent or surgically inaccessible tumours. A dose of 3000 to 3500 cGy in 15–18 fractions is delivered over 3–3.5 weeks. The tumour regresses slowly over about a year. Radiotherapy is also used for intracranial extension when the tumour derives its blood supply from the internal carotid system. The use of radiotherapy is controversial. Some reserve it for large tumours with intracranial extension or recurrent inoperable tumours, while others believe it should be avoided due to the risk of malignancy development in the young nasopharynx.

Hormonal Therapy

Since juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma occurs in young males at puberty due to activation of male hormones (testosterone), oestrogen (diethylstilbestrol) therapy was once used to reduce the size and vascularity of the tumour. However, it was stopped because it caused feminine changes in boys. Adjuvant oral flutamide (an androgen blocker) in post-pubertal patients can sometimes shrink the tumour if given for 6 weeks before surgery, but overall results remain limited.

Chemotherapy

Very aggressive recurrent tumours and residual lesions have been treated with chemotherapy, using combinations of doxorubicin, vincristine and dacarbazine. Chemotherapy can arrest growth and cause some regression, but does not achieve complete tumour eradication. Recurrence of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma is not uncommon, occurring in up to 35% of cases. Management options for recurrence include observation, revision surgery, radiotherapy, hormonal therapy, and chemotherapy.

———— End of the chapter ————

High-Yield Points for Quick Revision

- Who?: Adolescent males, 10-20 years.

- What?: Benign, highly vascular tumour of the nasopharynx.

- Where?: Originates from the superior margin of the sphenopalatine foramen.

- The most common benign nasopharyngeal tumour in adolescent males.

- Histologically benign, clinically aggressive.

- Key Symptoms: Recurrent, profuse epistaxis and progressive nasal obstruction.

- Viva Questions: Why is a biopsy avoided? What is the Holman-Miller sign? What is the “salt-and-pepper” sign? Why is JNA a surgical challenge?

- Investigations: CT scan is the investigation of choice. MRI is better for soft tissue extension. Angiography for pre-operative embolisation.

- Pathology: Composed of fibrous tissue and blood vessels lacking a muscular layer.

- Treatment of choice: Endoscopic surgical excision + pre-op embolisation.

- Recurrence rate: ~30–35%.

Clinical Scenarios for Viva and Practical Exams

Scenario 1: Emergency Department Presentation

Case: A 16-year-old boy comes to the emergency department with severe nasal bleeding that started spontaneously 2 hours ago. His mother mentions he has had similar episodes over the past 6 months, along with difficulty breathing through his nose and changes in his voice.

Viva Questions:

- What is your differential diagnosis?

- What examination would you perform?

- What investigations would you order?

- How would you manage the acute bleeding?

Answer: Given the patient’s demographics (adolescent male) and presentation (recurrent epistaxis, nasal obstruction, voice changes), juvenile angiofibroma should be suspected. Examination should include nasal endoscopy to visualise any nasopharyngeal mass, but digital palpation should be avoided. Immediate management involves controlling bleeding with nasal packing, IV access, and hemodynamic monitoring. Definitive diagnosis requires a contrast-enhanced CT scan once bleeding is controlled.

Scenario 2: Radiology Discussion

Case: CT scan of a 14-year-old boy shows a contrast-enhancing mass in the nasopharynx with anterior bowing of the posterior wall of the right maxillary sinus.

Viva Questions:

- What is the significance of the anterior bowing?

- What other radiological signs would you look for?

- What additional imaging might be required?

- How would you stage this tumor?

Answer: The anterior bowing represents the pathognomonic antral sign (Holman-Miller sign) diagnostic of juvenile angiofibroma. Additional signs include pterygoid plate bowing, vidian canal widening, and pterygopalatine fossa expansion. MRI would be needed if intracranial extension is suspected. Staging follows Radkowski’s classification based on the extent of spread.

Scenario 3: Treatment Planning

Case: A 15-year-old presents with Stage 2b juvenile angiofibroma with orbital involvement.

Viva Questions:

- What treatment options are available?

- What pre-operative preparations are necessary?

- Which surgical approach would you choose?

- What are the potential complications?

Answer: Surgical excision remains the treatment of choice. Pre-operative embolization should be performed 24-48 hours before surgery. For Stage 2b with orbital involvement, endoscopic approach may be challenging, potentially requiring combined endoscopic-external approach. Complications include bleeding, CSF leak, diplopia, and recurrence. Complete excision with pterygoid drilling is essential.

Scenario 4: Post-operative Follow-up

Case: A patient underwent endoscopic resection of juvenile angiofibroma 6 months ago and now presents with recurrent nasal obstruction.

Viva Questions:

- What is your concern?

- How would you evaluate this patient?

- What are the risk factors for recurrence?

- What management options are available?

Answer: Recurrence is a major concern given the symptoms. Evaluation requires nasal endoscopy and contrast CT scan to assess for residual/recurrent disease. Risk factors include incomplete excision, inadequate pterygoid drilling, and extensive original disease. Management options include revision surgery (preferred), radiotherapy for inoperable cases, or observation for small asymptomatic recurrences.

MCQs

- A 15-year-old male presents with a history of recurrent epistaxis and progressive nasal obstruction. On examination, a reddish mass is seen in the nasopharynx. Which of the following is the most appropriate initial investigation? A) Incisional biopsy B) Excisional biopsy C) Contrast-enhanced CT scan D) MRI brain E) Nasal endoscopy

- The “Holman-Miller sign” is a characteristic radiological finding associated with which of the following conditions? A) Wegener’s granulomatosis B) Antrochoanal polyp C) Juvenile Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma D) Sinonasal papilloma E) Rhabdomyosarcoma

- The primary blood supply to a Juvenile Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma is usually from a branch of which artery? A) Internal Carotid Artery B) External Carotid Artery C) Facial Artery D) Sphenopalatine Artery E) All of the above

- A 16-year-old boy is diagnosed with a Juvenile Angiofibroma. Which of the following is the most crucial step to reduce intra-operative blood loss? A) Pre-operative radiotherapy B) Pre-operative embolisation C) Pre-operative hormonal therapy D) Hypotensive anaesthesia E) Surgical ligation of feeding vessels

- The “salt-and-pepper” appearance on MRI is a characteristic finding in JNA, but it is also associated with which other tumour? A) Olfactory neuroblastoma B) Plasmacytoma C) Paraganglioma D) Sinonasal carcinoma E) Lymphoma

- Which of the following is NOT a surgical approach for Juvenile Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma? A) Transpalatal approach B) Lateral rhinotomy C) Midfacial degloving D) Subcranial approach E) Endoscopic approach

- A 14-year-old male presents with a JNA, which has extended into the infratemporal fossa. According to the Radkowski classification, this tumour would be staged as: A) Stage I B) Stage II C) Stage III D) Stage IV E) Stage V

- Which of the following is a false statement regarding Juvenile Angiofibroma? A) It is a benign tumour. B) It is a highly vascular tumour. C) It is common in females. D) It is associated with recurrent epistaxis. E) It has no true capsule.

- The primary reason for severe bleeding during the surgical removal of a JNA is that its blood vessels: A) Have a thin muscular layer. B) Have a thick muscular layer. C) Lack a muscular layer. D) Are supplied by multiple arteries. E) Are prone to spontaneous rupture.

- A young male patient undergoes surgery for JNA. A post-operative CT scan shows two parallel lines caused by the separation of the pterygoid plates. This sign is known as: A) Holman-Miller sign B) Ramaharan’s sign C) Chopstick sign D) Trismus sign E) Frog facies

MCQ Answer Key and Explanations

- C) Contrast-enhanced CT scan. Biopsy is contraindicated due to the risk of severe haemorrhage. A contrast-enhanced CT scan is the investigation of choice to confirm the diagnosis, determine the extent of the tumour, and plan for surgery.

- C) Juvenile Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma. The Holman-Miller sign, which is the anterior bowing of the posterior wall of the maxillary sinus, is pathognomonic for JNA.

- B) External Carotid Artery. The primary blood supply to JNA is from the external carotid artery system, particularly the internal maxillary artery. The internal carotid artery system provides blood supply only in larger, more advanced tumours.

- B) Pre-operative embolisation. Embolisation is the most effective way to reduce blood loss and is now a standard part of JNA management.

- C) Paraganglioma. The “salt-and-pepper” appearance on MRI is characteristic of both JNA (on T2 images) and paragangliomas (on T1 images).

- D) Subcranial approach. All other options are well-described surgical approaches for JNA, with the choice depending on the tumour’s extent. A subcranial approach is a different surgical technique used for other skull base pathologies.

- C) Stage III. According to the Radkowski classification, extension into the infratemporal fossa is a key feature of Stage III tumours.

- C) It is common in females. This is a false statement. JNA is almost exclusively a tumour of adolescent males.

- C) Lack a muscular layer. The unique vascular structure of JNA, where the blood vessels lack a muscular layer, prevents them from constricting and is the main reason for profuse bleeding during surgery.

- C) Chopstick sign. This is a post-operative radiological sign caused by the separation of the pterygoid plates after drilling the pterygoid base during surgery to reduce recurrence.

Frequently Asked Questions in Viva

- What is the average age of a patient with Juvenile Angiofibroma? The average age is around 14 years, with the tumour typically affecting adolescent males between 7 and 19 years of age.

- Can a biopsy be performed to diagnose JNA? Biopsy is generally avoided due to the high risk of catastrophic haemorrhage. Diagnosis is made based on clinical findings and imaging (CT and MRI).

- Why is JNA considered a benign tumour if it is so aggressive? JNA is benign because it does not metastasize (spread to distant parts of the body). Its aggression is local; it spreads by invading and destroying nearby structures through natural openings.

- What is the definitive treatment for JNA? The definitive treatment is surgical excision. Pre-operative embolisation is a standard practice to reduce intra-operative blood loss.

- Is radiotherapy a good treatment option for JNA? Radiotherapy is reserved for specific cases, such as large tumours with intracranial extension or recurrent, inoperable tumours. It is controversial due to the potential risk of inducing malignancy in young patients.

- How does JNA cause hearing loss? JNA causes conductive hearing loss and otitis media with effusion by obstructing the Eustachian tube, which is located in the nasopharynx.

- Why is JNA only found in males? JNA has a strong hormonal link. The presence of androgen receptors in the tumour and its occurrence in adolescent males during puberty strongly suggest that male hormones, particularly testosterone, play a crucial role in its aetiology.

———— End————

Download full PDF Link:

Juvenile Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma Best Lecture Notes Dr Rahul Bagla ENT Textbook

Reference Textbooks.

- Scott-Brown, Textbook of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery.

- Cummings, Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery.

- Stell and Maran’s, Textbook of Head and Neck Surgery and Oncology.

- Ballenger’s, Otorhinolaryngology Head And Neck Surgery

- Susan Standring, Gray’s Anatomy.

- Frank H. Netter, Atlas of Human Anatomy.

- B.D. Chaurasiya, Human Anatomy.

- P L Dhingra, Textbook of Diseases of Ear, Nose and Throat.

- Hazarika P, Textbook of Ear Nose Throat And Head Neck Surgery Clinical Practical.

- Mohan Bansal, Textbook of Diseases of Ear, Nose and Throat Head and Neck Surgery.

- Hans Behrbohm, Textbook of Ear, Nose, and Throat Diseases With Head and Neck Surgery.

- Logan Turner, Textbook of Diseases of The Nose, Throat and Ear Head And Neck Surgery.

- Arnold, U. Ganzer, Textbook of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery.

- Ganong’s Review of Medical Physiology.

- Guyton & Hall Textbook of Medical Physiology.

Author:

Dr. Rahul Bagla

MBBS (MAMC, Delhi) MS ENT (UCMS, Delhi)

Fellow Rhinoplasty & Facial Plastic Surgery.

Renowned Teaching Faculty

Mail: msrahulbagla@gmail.com

India

———– Follow us on social media ————

- Follow our Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/Dr.Rahul.Bagla.UCMS

- Follow our Instagram page:https://www.instagram.com/dr.rahulbagla/

- Subscribe to our Youtube channel: https://www.youtube.com/@Drrahulbagla

- Please read. Juvenile Angiofibroma. https://www.entlecture.com/juvenile-angiofibroma/

- Please read. Tumours of Hypopharynx . https://www.entlecture.com/tumours-of-the-hypopharynx/

- Please read. Anatomy of Oesophagus. https://www.entlecture.com/anatomy-of-oesophagus/

Keywords: Juvenile Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma, Angiofibroma, Testosterone Dependency Theory, Pituitary-gonadal axis theory, First Branchial Arch Artery Theory, Extensions, Clinical features, Embolization, Holman-Miller Sign, juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma symptoms, causes of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma, treatment options for JNA tumour, early signs of nasopharyngeal angiofibroma, surgical removal of JNA tumours, risk factors for juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma, diagnostic methods for JNA tumours, post-surgery care for nasopharyngeal angiofibroma, recurrence of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma, role of imaging in JNA diagnosis, Understanding Juvenile Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma: Symptoms and Treatment, Early Detection of JNA Tumors: What Parents Should Know, Surgical and Non-Surgical Approaches to Juvenile Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma, Juvenile Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma: Causes, Risks, and Diagnosis Explained, Treatment Journey for JNA Tumors: From Diagnosis to Recovery, Recognizing the Signs of Juvenile Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma in Teenagers, Advanced Imaging Techniques for JNA Diagnosis and Management, Post-Surgical Care Tips for Juvenile Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma Patients, Preventing Recurrence of Juvenile Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma: Expert Advice, Comprehensive Guide to Juvenile Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma for Families.

Thanks a lot.