Tonsillectomy

Tonsillectomy involves the complete surgical removal of the palatine tonsils, along with their fibrous capsule. This dissection occurs in the avascular peritonsillar space, situated between the tonsil capsule and the muscular wall of the pharynx. Often, tonsillectomy is performed in conjunction with an adenoidectomy (removal of adenoids), depending on the patient’s condition and indications.

Conversely, tonsillotomy (also known as intracapsular tonsillectomy or partial tonsillectomy) involves the partial removal of tonsillar lymphoid tissue, intentionally leaving the tonsil capsule intact. This technique aims to preserve the protective barrier around the tonsillar bed, potentially reducing pain and the risk of bleeding.

Indications for Tonsillectomy

Indications for tonsillectomy are broadly categorised into absolute and relative, based on the severity and impact of tonsillar disease. Understanding these distinctions is crucial for ENT viva questions and clinical scenarios.

1. Absolute Indications

Absolute indications mandate tonsillectomy due to significant health risks or severe functional impairment.

- Recurrent Throat Infections: This is the most prevalent indication for tonsillectomy, significantly impacting a patient’s quality of life. The Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), influenced by the landmark Paradise trial, provides specific criteria. A “sore throat attack” is defined by the presence of all four of the following:

- Fever ∘F (∘C)

- Cervical lymphadenopathy (enlarged neck lymph nodes)

- Tonsillar exudates (pus or white spots on tonsils)

- Positive culture for Beta-hemolytic Streptococcus.

Specific frequencies further define recurrent infections over time:

-

- Seven or more episodes in the preceding 1 year, OR

- Five episodes per year for the preceding 2 years, OR

- Three episodes per year for the preceding 3 years, OR

- Two weeks or more of lost school or work in 1 year due to tonsillitis.

- Peritonsillar Abscess (PTA): A collection of pus behind the tonsil.

- In adults, a second episode of peritonsillar abscess is considered an absolute indication.

- In children, tonsillectomy is typically performed 4-6 weeks after the acute infection and abscess have been successfully treated.

- Hot tonsillectomy (tonsillectomy during active PTA) is generally not recommended due to a significantly increased risk of excessive bleeding during surgery. However, in specific cases of airway compromise or uncontrolled infection, it might be considered with extreme caution.

- Febrile Seizures due to Tonsillitis: If tonsillitis consistently triggers febrile seizures.

- Hypertrophy of Tonsils (Tonsillar Hypertrophy): Significantly enlarged tonsils can lead to various complications.

- Airway Obstruction: The most common and serious consequence, often manifesting as obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).

- Difficulty in Deglutition (Swallowing): Large tonsils can physically impede the passage of food.

- Interference with Speech: While less common, very large tonsils can affect vocal resonance. Hyponasality (a “stuffy nose” quality) is typically associated with Grade IV tonsillar hypertrophy. Rarely, hypernasality may occur if the enlarged tonsils interfere with the movement of the soft palate.

- Suspicion of Malignancy: A unilaterally enlarged tonsil, especially if rapidly growing or associated with other suspicious signs (e.g., pain, weight loss), warrants immediate investigation.

- In children, a unilaterally enlarged tonsil may be a sign of lymphoma.

- In adults, it could suggest an epidermoid carcinoma.

- In such cases, a unilateral tonsillectomy serves as an excision biopsy for definitive diagnosis.

Indications for Unilateral Tonsillectomy

-

- Embedded or Impacted Tonsillar Foreign Body: Such as a fish bone, which cannot be easily removed by other means.

- Tonsillolith (Tonsil Stone): Large, symptomatic tonsilloliths causing chronic irritation or halitosis.

- Large Tonsillar Cyst: A significant cyst causing symptoms or suspicion.

- Suspected Malignancy of Tonsil: As described above, unilateral tonsillectomy is performed for diagnostic purposes.

Friedman Grading Scale for Tonsillar Size

The Friedman grading scale is commonly used to assess tonsillar hypertrophy, particularly in relation to obstructive sleep apnea. This grading is based on the visibility of the tonsils relative to the anterior pillars and midline.

| Grade | Description |

| Grade 0 | No tonsils visible (e.g., post-tonsillectomy) |

| Grade 1 | Tonsils are visible within the tonsillar fossa |

| Grade 2 | Tonsils visible beyond the anterior pillars |

| Grade 3 | Tonsils extending almost three-quarters of the way to the midline |

| Grade 4 | Tonsils meeting in the midline (“Kissing Tonsils”) |

Practical Tip for Viva: When presenting a case of tonsillar hypertrophy, always mention the Friedman grade and correlate it with the patient’s symptoms (e.g., “This patient has Grade 3 tonsillar hypertrophy, consistent with their complaints of snoring and witnessed apneas.”).

2. Relative Indications

Relative indications suggest tonsillectomy may be beneficial, but are not strictly mandatory.

- Chronic Tonsillitis: This refers to tonsillar infection persisting for more than three months, even after appropriate courses of antibiotics. Such refractory infection may necessitate tonsillectomy to resolve chronic symptoms.

- Antibiotic-Refractory Streptococcal Carriers: Some individuals carry Streptococcus pyogenes (Group A Strep) in their tonsils without active infection, yet they may transmit the bacteria to others. If these carriers do not respond to antibiotic therapy, particularly with a history of Acute Glomerulonephritis (AGN) or Rheumatic Fever, tonsillectomy might be considered to prevent further complications or spread.

- Halitosis (Bad Breath): Persistent halitosis can result from food debris, bacteria, and necrotic tissue accumulating in deep tonsillar crypts. If conservative measures fail, tonsillectomy can address the source of the odour.

- Hemorrhagic Tonsils: Recurrent bleeding from prominent vessels on the tonsil surface, refractory to local measures like cauterisation, may warrant tonsillectomy.

- PFAPA Syndrome: The syndrome of Periodic Fever, Aphthous Ulcers, Pharyngitis, and Cervical Adenopathy (PFAPA) is a rare inflammatory condition primarily affecting children under 5 years of age. The American Academy of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) guidelines recognise tonsillectomy as a potential therapeutic option for this syndrome.

- Other Localised Tonsil Conditions: Similar to absolute indications for unilateral cases, these can be relative indications for bilateral tonsillectomy if symptomatic or recurrent:

- Recurrent Tonsillar Cyst

- Recurrent Tonsilloliths causing symptoms

- Recurrent Foreign Body impaction in the tonsil that is difficult to remove.

- Diphtheria Carriers: Patients who harbour Corynebacterium diphtheriae and do not respond to antibiotic eradication may undergo tonsillectomy to eliminate the carrier state.

- Streptococcal Carriers: Similar to diphtheria carriers, these individuals can be a source of infection to others, and tonsillectomy may be considered in specific circumstances, especially in outbreak situations.

3. As a Part of Another Operation

Tonsillectomy may be performed as a preliminary step for other surgical procedures in the oropharynx.

- Palatopharyngoplasty (UPPP): Frequently combined with tonsillectomy, this procedure is performed for sleep apnea syndrome to widen the airway.

- Glossopharyngeal Neurectomy: The tonsil is removed first to expose the bed, allowing access to the ninth cranial nerve (glossopharyngeal nerve) for surgical severance, typically to treat severe neuralgias.

- Removal of the Styloid Process: An elongated styloid process (Eagle’s syndrome) can be accessed and removed through the tonsillar fossa after tonsillectomy.

Contraindications for Tonsillectomy

Certain conditions preclude tonsillectomy due to unacceptably high risks. Knowing these is vital for clinical case discussions and viva preparation.

- Haemoglobin Level less than 10 g%: Low haemoglobin indicates anaemia, which increases the risk of complications from blood loss during surgery.

- Presence of Acute Infection in Upper Respiratory Tract (URTI): This includes acute tonsillitis. Performing tonsillectomy during an active infection significantly increases the risk of excessive bleeding due to increased vascularity and inflammation, and can also increase the risk of postoperative infection. The procedure should be deferred until the acute infection has resolved, ideally for 2-3 weeks.

- Age less than 3 years: In very young children, their total blood volume is relatively small. The potential blood loss during conventional tonsillectomy might be too significant, potentially necessitating blood transfusions. However, this is a relative contraindication, and in cases of severe airway obstruction (e.g., severe OSA), surgery may be performed earlier, albeit with greater caution and specialised pediatric anaesthetic support.

- Overt or Submucous Cleft Palate: Tonsillectomy is a strong contraindication in these conditions. Removing the tonsils can exacerbate or cause velopharyngeal insufficiency (VPI), leading to hypernasal speech and nasal regurgitation of food, as the tonsils can sometimes partially compensate for poor soft palate function.

- Bleeding Disorders: Any known or suspected bleeding disorder significantly increases the risk of severe intraoperative and postoperative haemorrhage. Examples include:

- Leukemia

- Purpura

- Aplastic anemia

- Hemophilia

- However, for certain bleeding disorders like haemophilia, tonsillectomy can sometimes be performed with specialised techniques such as coblation or LASER with appropriate haematological support (e.g., factor replacement).

- During Times of Polio Epidemic: Historically, tonsillectomy was avoided during polio epidemics. The reasoning was that the raw area in the oropharynx after tonsillectomy might provide an easy entry point for the poliovirus into the bloodstream, increasing the risk of paralytic polio. While polio is largely eradicated in many parts of the world, this historical contraindication highlights the importance of considering widespread infectious diseases.

- Uncontrolled Systemic Diseases: Patients with poorly controlled systemic conditions face higher anesthetic and surgical risks. These include:

- Uncontrolled diabetes mellitus

- Uncontrolled cardiac disease (e.g., severe arrhythmias, unstable angina)

- Uncontrolled hypertension

- Uncontrolled asthma

- Surgery should be deferred until these conditions are optimally managed.

- Menstruation: Tonsillectomy is traditionally avoided during the period of menses due to a theoretical increased risk of bleeding. While not an absolute contraindication, it’s often preferred to schedule surgery outside this period if possible.

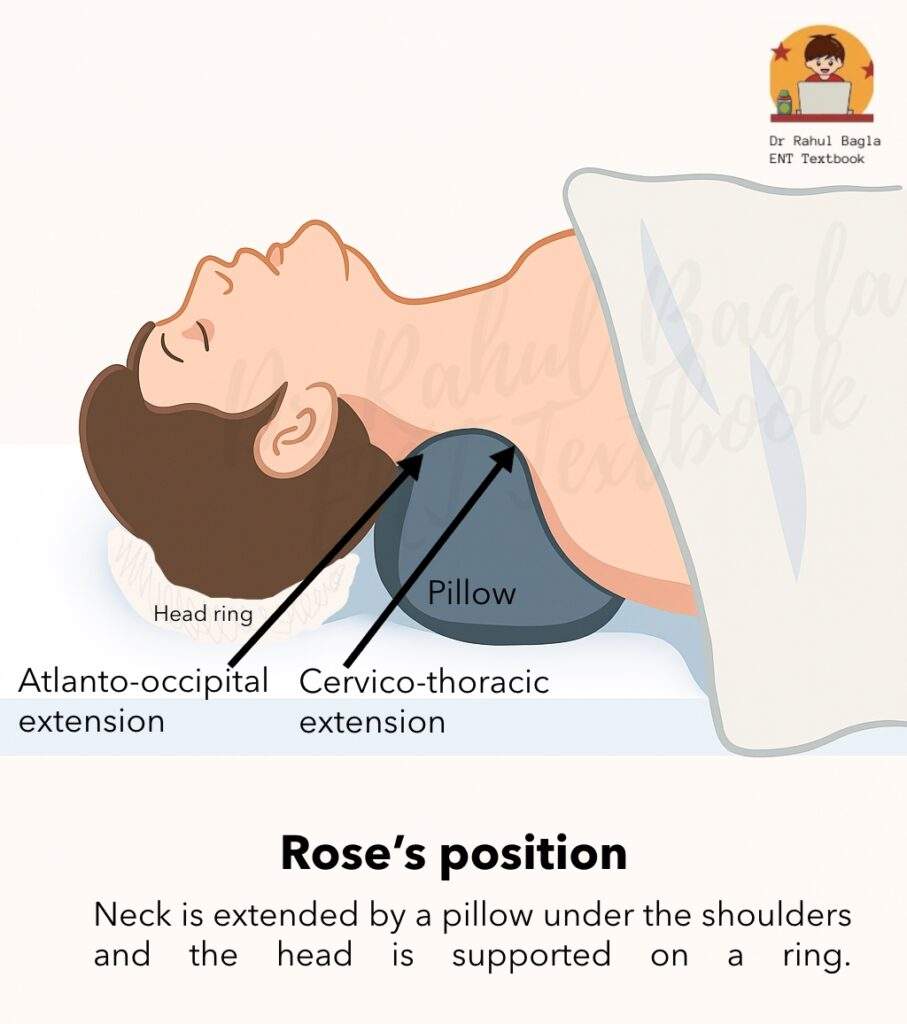

- Cervical Spine Pathologies: Conditions affecting the cervical spine may make positioning the patient for surgery (especially in Rose’s position) difficult or dangerous, potentially leading to spinal cord injury.

Surgical Steps: Cold Steel Tonsillectomy (Dissection and Snare Method)

The cold steel dissection and snare method remains a widely taught and performed technique. Understanding each step is crucial for MBBS practical exams and viva scenarios.

Detailed Steps

- Anesthesia:

- Usually performed under general anaesthesia with endotracheal intubation, providing a secure airway.

- In selected adult cases, it may be performed under local anaesthesia with sedation, though this is less common due to patient comfort and visualisation challenges.

- Position:

- The patient is typically placed in Rose’s position (also known as the Tonsillectomy position).

- The patient lies supine with a pillow or shoulder bag placed under the shoulders. This manoeuvre extends the head and neck at the atlanto-occipital and cervicothoracic joints.

- A rubber ring is placed under the head to stabilise it.

- Rationale for Rose’s position: This position allows for optimal visualisation of the oral cavity and oropharynx. Critically, it creates a dependent position for the nasopharynx, which helps to prevent the aspiration of blood and secretions into the trachea during surgery.

- The surgeon usually sits behind the patient’s head, using a headlight for illumination.

- Application of Boyle-Davis Mouth Gag:

- This specialised mouth gag is inserted to hold the mouth open and retract the tongue, providing excellent exposure of the tonsils and oropharynx.

- It is then typically fixed in place using Draffin bipods and a plate, freeing both of the surgeon’s hands to operate.

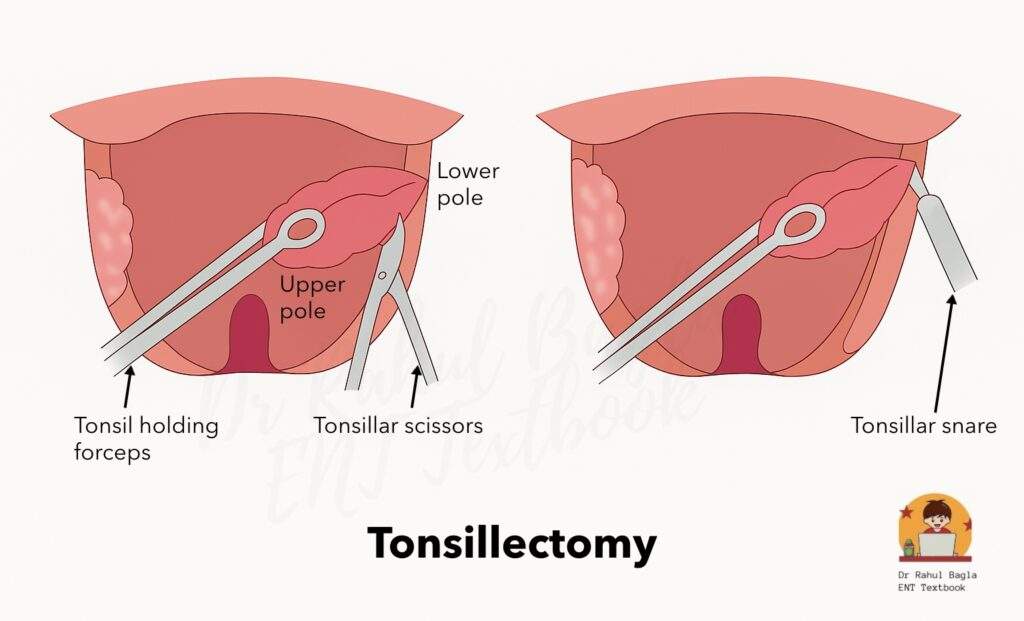

- Tonsil Grasp and Medial Traction:

- The tonsil to be removed is grasped firmly with a Denis Browne’s tonsil-holding forceps or a similar sturdy tonsil-holding forceps.

- Gentle but firm medial traction is applied to pull the tonsil towards the midline, stretching the anterior pillar and highlighting the mucocutaneous junction.

- Incision:

- An initial incision is made in the mucous membrane where it reflects from the tonsil onto the anterior pillar.

- A sickle knife or toothed tonsillar forceps (Waugh’s forceps) is commonly used for this.

- The incision may be extended along the upper pole to the mucous membrane between the tonsil and the posterior pillar, outlining the tonsil’s attachment.

- Separation of the Upper Pole:

- A blunt curved scissor (e.g., Tonsil Scissor) or a tonsillar dissector is used to carefully separate the upper pole of the tonsil from the peritonsillar tissue. This marks the beginning of identifying the correct dissection plane.

- A blunt curved scissor (e.g., Tonsil Scissor) or a tonsillar dissector is used to carefully separate the upper pole of the tonsil from the peritonsillar tissue. This marks the beginning of identifying the correct dissection plane.

- Application of Downward and Medial Traction:

- The tonsil is now held firmly, often at its upper pole, and consistent downward and medial traction is applied. This manoeuvre helps to keep the peritonsillar space taut and aids in identifying the avascular plane.

- Dissection in the Avascular Plane:

- Using a tonsillar dissector (e.g., Lack’s dissector or Negus dissector), dissection is meticulously continued in the avascular plane of the peritonsillar space.

- This critical plane lies between the true capsule of the tonsil and the fascia covering the superior constrictor muscle.

- A properly identified plane appears as a shiny, white line, indicating the correct anatomical layer and minimizing bleeding.

- Continuation of Dissection to the Lower Pole:

- The dissection proceeds carefully, following this avascular plane, from the upper pole downwards towards the lower pole of the tonsil.

- Dissection continues until only the tonsillar pedicle remains attached. This pedicle is the final attachment of the tonsil and contains its main blood supply.

- Cutting the Tonsillar Pedicle with Eve’s Tonsillar Snare:

- The tonsillar pedicle, containing the tonsillar artery, paratonsillar vein, lymphatics, and sometimes the plica triangularis mucosal fold, is now isolated.

- An Eve’s tonsillar snare (or a similar surgical snare) is applied around the pedicle.

- The snare mechanism involves crushing the pedicle and then slowly cutting it. This crushing action helps to occlude the lumens of the vessels within the pedicle, thereby aiding in hemostasis and reducing blood loss.

- Hemostasis:

- After the tonsil is removed, the tonsillar fossa is immediately packed with a gauze swab to apply pressure and control bleeding.

- To achieve definitive hemostasis, the surgeon inspects the tonsillar bed for any active bleeders.

- Bleeding vessels may be managed by:

- Ligation: Tying off the bleeding vessel with sutures.

- Electrocautery: Using electrical current to coagulate and seal the bleeding vessels.

- Packing: Continued pressure with gauze packs.

- Repeat on the Other Side:

- Once satisfactory hemostasis is achieved in the first tonsillar fossa, the entire procedure is repeated for the contralateral tonsil.

Practical Tip for Viva: When asked to describe tonsillectomy steps, emphasise the identification of the avascular plane and the importance of hemostasis. Examiners often focus on these critical aspects.

Postoperative Care

Effective postoperative care is paramount for minimising complications and ensuring a smooth recovery.

1. Immediate General Care

- Positioning: Keep the patient in the “coma position” (left lateral position with right knee flexed towards the abdomen) until they are fully recovered from general anaesthesia. This position helps prevent aspiration of blood or secretions.

- Monitoring for Bleeding: Continuously monitor for signs of bleeding from the nose and mouth.

- Excessive swallowing or frequent vomiting of blood are crucial early indicators of active bleeding from the tonsillar bed. These signs warrant immediate attention.

- Vital Signs Monitoring: Regularly check vital signs, including pulse, respiration rate, and blood pressure. A rising pulse and falling blood pressure may indicate significant blood loss.

- Close Observation for OSA Patients: Patients who underwent tonsillectomy for obstructive sleep apnea require particularly close monitoring in the immediate postoperative period for signs of airway compromise. They may be more susceptible to respiratory depression from analgesics.

2. Diet

- Once the patient is fully recovered from anaesthesia and the gag reflex returns, liquids are permitted. Cold liquids like milk or ice cream are often soothing.

- Sucking on ice cubes can also provide significant pain relief and help reduce swelling.

- The diet is gradually advanced from soft to solid foods.

- On the second day, patients can typically consume soft foods such as custard, jelly, soft-boiled eggs, or slices of bread soaked in milk.

- Encourage plenty of fluids to maintain hydration and prevent dehydration, which can worsen pain.

3. Oral Hygiene

- Patients should be encouraged to perform Condy’s (potassium permanganate) or salt water gargles three to four times a day starting from the day after surgery. This helps in wound cleaning and reduces bacterial load.

- A simple mouth rinse with plain water after every meal helps to keep the mouth clean and remove food debris.

4. Analgesics

- Pain, both localised in the throat and referred to the ear (due to irritation of the glossopharyngeal nerve), is common.

- Paracetamol (acetaminophen) is the primary analgesic of choice.

- Administer analgesics approximately 30 minutes before meals to facilitate easier eating.

- Crucially, avoid aspirin and ibuprofen (NSAIDs) in the postoperative period.

- Aspirin significantly increases the risk of primary haemorrhage by reducing platelet adhesiveness and prolonging bleeding time.

- Furthermore, aspirin is contraindicated in children less than 16 years of age due to the risk of Reye’s syndrome.

- Ibuprofen and other NSAIDs also carry a risk of increased bleeding.

5. Antibiotics

- A suitable oral or intravenous antibiotic may be prescribed for approximately one week post-surgery to prevent postoperative infection, though routine antibiotic use is debated and depends on surgical preference and patient risk factors.

6. Steroid Treatment

- Steroid treatment, particularly intravenous dexamethasone, has gained widespread acceptance in the perioperative management of tonsillectomy.

- A single intravenous dose of dexamethasone administered intraoperatively has been shown in recent trials to be safe and effective in reducing postoperative pain, nausea, vomiting, and overall morbidity, especially in paediatric tonsillectomy patients. It helps to reduce inflammation and swelling.

7. Discharge and Recovery

- Patients are typically discharged home 24 hours after the operation, provided there are no complications and they are stable.

- Patients can usually resume their normal activities, including school or light work, within 2 weeks post-surgery. Strenuous activities and contact sports should be avoided for longer.

Complications of Tonsillectomy

Complications can be broadly categorised into perioperative (occurring during or immediately after surgery) and postoperative (occurring later). Knowledge of these complications is essential for NEET PG MCQs and clinical management.

A. Perioperative Complications (Intraoperative)

These occur during the surgery itself.

- Primary Haemorrhage:

- Defined as bleeding occurring at the time of operation, within 24 hours of surgery (some definitions include only intraoperative bleeding).

- Some blood loss is expected during tonsillectomy. However, excessive bleeding can occur due to:

- Recent peritonsillar abscess or acute tonsillitis (due to increased vascularity).

- Undiagnosed coagulation defects.

- Injury to a large tonsillar branch of the facial artery.

- Rarely, injury to an aberrant internal carotid artery occurs, though this is exceedingly rare and usually means the dissection plane was incorrect.

- Management:

- Direct pressure with gauze.

- Ligation or cauterisation of bleeding vessels in the tonsillar fossa.

- In rare, uncontrollable cases, ligation of the ipsilateral external carotid artery may be necessary.

- Injury to Adjacent Structures: This usually results from poor surgical technique or inadequate visualisation. Structures at risk include: lips, teeth, tonsillar pillars, uvula, soft palate, tongue, or superior constrictor muscle.

- Dislocation of the Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ): Can occur during the insertion or prolonged use of the mouth gag, especially if excessive force is applied or the patient has pre-existing TMJ issues.

B. Postoperative Complications

These are complications that arise after the immediate perioperative period. They are further divided into early and intermediate/late.

1. Early Complications (within 24 hours)

- Primary/Reactionary Haemorrhage:

- Occurs within the first 24 hours after surgery, most commonly within the first 8 hours.

- Incidence rates vary from 0.1% to 5.8% in different studies.

- Causes: Often attributed to:

- Inadequate surgical hemostasis.

- Dislodgement of a blood clot from the lumen of a vessel (e.g., during coughing or vomiting).

- Slippage of a ligature (suture tie) from a vessel.

- Reopening of vessels due to increased blood pressure (e.g., from pain or exertion) or retching/coughing.

- Analogy: Compare with postpartum uterine bleeding, where the failure of the uterus to contract (analogous to clot dislodgement or vessel not contracting) leads to bleeding. The superior constrictor muscle normally helps to compress vessels in the tonsillar bed; a clot prevents this “clipping action.”

- Clinical Presentation: Patients may present with active bleeding from the mouth or nose, frequent swallowing, or vomiting of fresh or clotted blood.

- Management:

- Simple measures: Removal of visible clot, application of direct pressure to the tonsillar fossa with a gauze swab, topical application of vasoconstrictors (e.g., dilute adrenaline).

- If these fail, the patient requires re-exploration under general anesthesia for:

- Ligation or electrocoagulation of the bleeding vessel(s).

- Suturing of the tonsillar pillars over a gauze pack (packing the fossa).

2. Intermediate/Late Complications (after 24 hours, typically 5th-10th day)

- Secondary Haemorrhage:

- The most common and feared late complication.

- Typically occurs between the 5th to 10th postoperative day, though it can happen later.

- Cause: Primarily due to sepsis (infection) in the tonsillar fossa and subsequent premature separation of the fibrinous membrane (slough) covering the tonsillar bed. The infection erodes the vessel walls, leading to bleeding.

- Clinical Presentation: Often heralded by blood-stained sputum. However, it can rapidly become profuse and life-threatening.

- Management:

- Initial measures: Removal of clot, topical application of dilute adrenaline or hydrogen peroxide, and direct pressure usually suffice for minor bleeds.

- For profuse bleeding, immediate re-admission and re-exploration under general anaesthesia is required.

- The bleeding vessel is identified and electrocoagulated. Ligation of vessels can be challenging due to the friable and inflamed tissue.

- Sometimes, approximation of the pillars with mattress sutures (Pillar sutures) may be required to compress the bleeding area.

- In very severe, uncontrollable cases, external carotid artery ligation may be necessary as a last resort.

- Blood transfusion (whole blood or plasma) may be required depending on the blood loss and patient’s hemodynamic status.

- Systemic antibiotics are crucial for controlling the underlying infection.

- Infection:

- Infection of the tonsillar fossa is common, presenting as pain, fever, and foul breath. It can sometimes progress to:

- Parapharyngeal abscess: A deep neck space infection.

- Otitis Media: Middle ear infection, often due to Eustachian tube dysfunction or spread of infection.

- Infection of the tonsillar fossa is common, presenting as pain, fever, and foul breath. It can sometimes progress to:

- Lung Complications:

- Aspiration of blood, mucus, or tissue fragments during or after surgery can lead to:

- Atelectasis: Collapse of lung tissue.

- Lung Abscess: A localized collection of pus in the lung.

- Pneumonia: Inflammation of the lung.

- Aspiration of blood, mucus, or tissue fragments during or after surgery can lead to:

- Subacute Bacterial Endocarditis (SABE)/Infective Endocarditis (IE):

- Tonsillectomy can cause a transient bacteremia.

- While rare, this bacteremia can lead to infective endocarditis (IE) in susceptible individuals, particularly those with:

- Abnormal (leaky or narrow) heart valves (e.g., rheumatic heart disease).

- Artificial (prosthetic) heart valves.

- Certain congenital heart defects.

- Patients with pacemaker leads.

- Prophylactic antibiotics are often considered for high-risk cardiac patients undergoing tonsillectomy, though guidelines have become more stringent.

- Scarring in Soft Palate and Pillars:

- Excessive scarring can occur, potentially leading to discomfort or affecting speech.

- Tonsillar Remnants (Tonsil Tags):

- Inadequate or incomplete surgical removal of tonsillar tissue can leave behind small “tonsil tags” or lymphoid tissue.

- These remnants can later become infected, leading to recurrent tonsillitis, essentially negating the purpose of the tonsillectomy.

- Practical Tip: During tonsillectomy, ensure complete removal, paying particular attention to the lymphoid tissue often found in the plica triangularis near the lower pole, as this is a common site for remnants.

- Hypertrophy of Lingual Tonsil:

- This is a late, compensatory complication. After removal of the palatine tonsils, the lingual tonsil (at the base of the tongue) may hypertrophy in an attempt to compensate for the lost lymphoid tissue.

- This can sometimes cause globus sensation, discomfort, or even contribute to sleep-disordered breathing.

- Aspiration of Blood:

- Can occur during or after surgery, potentially leading to respiratory distress or lung complications.

- Facial Oedema:

- Some patients, particularly children, may experience temporary swelling of the face, especially around the eyelids. This is usually self-limiting.

- Surgical Emphysema:

- Rarely, injury to the superior constrictor muscle or other pharyngeal muscles can lead to air tracking into the neck tissues, causing surgical emphysema (crepitus on palpation). This typically resolves spontaneously.

———— End of the chapter ————

High-Yield Points for Quick Revision

These points are frequently tested in NEET PG MCQs and university theory/viva exams.

- Most Common Indication: Recurrent throat infections (based on SIGN/Paradise criteria).

- Absolute vs. Relative: Know the key differentiators (e.g., airway obstruction is absolute, halitosis is relative).

- Friedman Grading: Crucial for tonsillar hypertrophy and OSA assessment. Grade 4 is “kissing tonsils.”

- Hot Tonsillectomy: Generally avoided in acute PTA due to bleeding risk.

- Contraindications:

- Cleft Palate (Overt/Submucous): Risk of velopharyngeal insufficiency (VPI).

- Bleeding Disorders: High risk of haemorrhage.

- Age < 3 years: Relative contraindication due to blood volume/loss concerns.

- Rose’s Position: Key for preventing aspiration.

- Avascular Plane: Between the tonsil capsule and the superior constrictor muscle fascia. Appears white.

- Eve’s Snare: Crushing and cutting action for hemostasis.

- Postoperative Bleeding:

- Primary/Reactionary: Within 24 hours, often surgical error, clot dislodgement.

- Secondary: 5-10 days post-op, due to infection and slough separation. More common and potentially more severe.

- Analgesia: Paracetamol preferred. Avoid Aspirin/NSAIDs due to bleeding risk and Reye’s syndrome (Aspirin in children).

- Steroids (Dexamethasone): Reduces pain, nausea, vomiting post-op.

- Lingual Tonsil Hypertrophy: Late compensatory complication.

- Plica Triangularis: Common site for tonsillar remnants.

- Swallowing/Vomiting Blood: Key sign of postoperative haemorrhage.

Clinical-Based Questions

These scenarios mimic practical exam and viva questions, assessing your ability to apply knowledge.

Scenario 1: A 7-year-old boy presents with a history of recurrent sore throats. His parents report 6 episodes in the last year, each associated with fever, pus on tonsils, and neck swelling, requiring antibiotic courses. They also note he snores loudly and occasionally stops breathing during sleep. On examination, his tonsils are Grade 3 according to Friedman’s scale.

- Is this child a candidate for tonsillectomy? Justify your answer based on current guidelines.

- What specific indication (or indications) for tonsillectomy is most prominent in this case?

- What are the two most common early and late postoperative complications you would counsel the parents about?

Answer Key – Scenario 1:

- Yes, this child is a strong candidate for tonsillectomy.

- Justification: He meets the Paradise trial criteria for recurrent infections (6 episodes in 1 year, approaching the 7 episodes/year threshold, indicating significant burden). More importantly, the presence of loud snoring and witnessed apneas strongly suggests obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) due to tonsillar hypertrophy (Grade 3), which is an absolute indication for tonsillectomy. The combined presence of both recurrent infections and OSA significantly strengthens the indication.

- The most prominent indications are Obstructive Sleep Apnea (due to tonsillar hypertrophy) and Recurrent Tonsillitis.

- Early Postoperative Complication:

- Primary/Reactionary Hemorrhage: Occurs within 24 hours (most commonly first 8 hours). Counsel parents on signs like frequent swallowing, vomiting of blood, or active bleeding from the mouth/nose, and the need for immediate medical attention.

- Late Postoperative Complication:

- Secondary Hemorrhage: Occurs typically 5-10 days post-op, due to infection and slough separation. Counsel parents to watch for blood-stained saliva or active bleeding during this period, emphasizing strict adherence to oral hygiene and avoiding hard foods.

Scenario 2: A 35-year-old male presents with severe right-sided throat pain, fever, and trismus for 2 days. Examination reveals a swollen, medially displaced right tonsil with a bulging soft palate. He is diagnosed with a peritonsillar abscess. This is his first episode.

- What is the initial management for this patient?

- Would you recommend tonsillectomy immediately (hot tonsillectomy) for this patient? Why or why not?

- If the patient returns 6 months later with another episode of peritonsillar abscess on the same side, what would be your definitive management plan regarding tonsillectomy?

Answer Key – Scenario 2:

- Initial management:

- Incision and Drainage (I&D) of the peritonsillar abscess: This is the immediate definitive treatment to relieve pain, decompress the abscess, and drain the pus.

- Intravenous antibiotics: To cover likely bacterial pathogens (e.g., Streptococcus pyogenes, anaerobes).

- Pain management:

- Hydration: IV fluids if unable to take orally due to pain/trismus.

- No, I would not recommend immediate (hot) tonsillectomy for this patient.

- Reasoning: Performing tonsillectomy during an acute peritonsillar abscess (hot tonsillectomy) carries a significantly higher risk of severe intraoperative and postoperative bleeding due to increased vascularity and inflammation in the area. This is his first episode, and conservative management (I&D + antibiotics) is usually effective.

- If the patient returns 6 months later with a second episode of peritonsillar abscess on the same side, the definitive management plan would include interval tonsillectomy.

- After treating the acute second episode (I&D + antibiotics), tonsillectomy would be recommended approximately 4-6 weeks later, once the acute inflammation has subsided. A second attack of peritonsillar abscess is considered an absolute indication for tonsillectomy in adults to prevent further recurrence and potential complications.

Scenario 3: A 5-year-old girl is scheduled for tonsillectomy due to recurrent tonsillitis (meeting Paradise criteria). Her pre-operative blood tests show a hemoglobin level of 9.5 g/dL. She also has a history of a submucous cleft palate that was previously managed conservatively.

- Are there any contraindications to proceeding with tonsillectomy for this child? Explain your reasoning.

- If surgery is deferred due to one of these reasons, what immediate steps should be taken?

Answer Key – Scenario 3:

- Yes, there are two significant contraindications to proceeding with tonsillectomy for this child:

- Hemoglobin level < 10 g%: Her hemoglobin is 9.5 g/dL, which is below the safe threshold of 10 g/dL for tonsillectomy. Proceeding with surgery in an anemic child increases the risk of complications from blood loss and may necessitate blood transfusions.

- Submucous Cleft Palate: This is a strong contraindication. Removing the tonsils in a child with a submucous cleft palate (even if previously managed conservatively) significantly increases the risk of developing or worsening velopharyngeal insufficiency (VPI), leading to hypernasal speech and potentially nasal regurgitation, as the tonsils may be compensating for poor soft palate function.

- If surgery is deferred:

- For low hemoglobin: Investigate the cause of anemia (e.g., nutritional deficiency, chronic blood loss). Administer iron supplementation or other appropriate treatment to optimize hemoglobin levels before considering surgery.

- For submucous cleft palate: Re-evaluate the velopharyngeal function. Consider consultation with a cleft palate team or speech pathologist. If tonsillectomy is deemed absolutely necessary (e.g., severe airway obstruction) despite the cleft, an alternative approach like tonsillotomy (partial tonsillectomy) might be considered to preserve some tissue, or the patient and family must be thoroughly counselled about the very high risk of developing VPI and the need for future speech therapy or palatal surgery. In most cases, tonsillectomy would be considered absolutely contraindicated.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) in Viva

- Q: What is the main difference between tonsillectomy and tonsillotomy?

- A: Tonsillectomy is the complete removal of the tonsil and its capsule, while tonsillotomy is the partial removal of tonsil tissue, leaving the capsule intact.

- Q: Why is aspirin avoided after tonsillectomy?

- A: Aspirin (and other NSAIDs) are avoided because they increase the risk of bleeding by reducing platelet adhesiveness and prolonging bleeding time, and aspirin specifically carries the risk of Reye’s syndrome in children.

- Q: When is “hot tonsillectomy” performed?

- A: “Hot tonsillectomy” (during an acute peritonsillar abscess) is generally not recommended due to increased bleeding risk, but may be considered in very rare cases of severe airway obstruction.

- Q: What is the most common indication for tonsillectomy?

- A: Recurrent throat infections meeting specific frequency criteria (e.g., 7 episodes in 1 year, 5 per year for 2 years, or 3 per year for 3 years) is the most common indication. Obstructive sleep apnea due to tonsillar hypertrophy is also a very common and absolute indication.

- Q: What are the two types of postoperative haemorrhage after tonsillectomy, and when do they occur?

- A: Primary/Reactionary haemorrhage occurs within 24 hours (most commonly first 8 hours), while secondary haemorrhage occurs later, typically between the 5th and 10th postoperative day, usually due to infection.

- Q: Why is tonsillectomy contraindicated in patients with a cleft palate?

- A: Tonsillectomy is contraindicated in cleft palate (including submucous cleft) because it can lead to or worsen velopharyngeal insufficiency (VPI), resulting in hypernasal speech and nasal regurgitation.

———— End of the chapter ————

Download the full PDF Link:

Reference Textbooks.

- Scott-Brown, Textbook of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery.

- Cummings, Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery.

- Stell and Maran’s, Textbook of Head and Neck Surgery and Oncology.

- Ballenger’s, Otorhinolaryngology Head And Neck Surgery

- Susan Standring, Gray’s Anatomy.

- Frank H. Netter, Atlas of Human Anatomy.

- B.D. Chaurasiya, Human Anatomy.

- P L Dhingra, Textbook of Diseases of Ear, Nose and Throat.

- Hazarika P, Textbook of Ear Nose Throat And Head Neck Surgery Clinical Practical.

- Mohan Bansal, Textbook of Diseases of Ear, Nose and Throat Head and Neck Surgery.

- Hans Behrbohm, Textbook of Ear, Nose, and Throat Diseases With Head and Neck Surgery.

- Logan Turner, Textbook of Diseases of The Nose, Throat and Ear Head And Neck Surgery.

- Arnold, U. Ganzer, Textbook of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery.

- Ganong’s Review of Medical Physiology.

- Guyton & Hall Textbook of Medical Physiology.

Author:

Dr. Rahul Bagla

MBBS (MAMC, Delhi) MS ENT (UCMS, Delhi)

Fellow Rhinoplasty & Facial Plastic Surgery.

Renowned Teaching Faculty

Mail: msrahulbagla@gmail.com

India

———– Follow us on social media ————

- Follow our Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/Dr.Rahul.Bagla.UCMS

- Follow our Instagram page:https://www.instagram.com/dr.rahulbagla/

- Subscribe to our Youtube channel: https://www.youtube.com/@Drrahulbagla

- Please read. Juvenile Angiofibroma. https://www.entlecture.com/juvenile-angiofibroma/

- Please read. Tumours of Hypopharynx . https://www.entlecture.com/tumours-of-the-hypopharynx/

- Please read. Anatomy of Oesophagus. https://www.entlecture.com/anatomy-of-oesophagus/

Keywords: Learn everything about Tonsillectomy – indications, surgical steps, complications, and high-yield NEET PG MCQs. Perfect for MBBS and ENT PG students. ENT topics for NEET PG, MBBS ENT notesENT viva questions, Tonsillectomy surgery steps, Tonsillectomy complications NEET PG, Friedman grading of tonsils, Tonsillectomy indications CBME, ENT topics for NEET PG, MBBS ENT notes, Tonsillectomy indications, Tonsillectomy contraindications, Tonsillectomy surgical steps, Postoperative care tonsillectomy, Tonsillectomy complications, Recurrent tonsillitis treatment, Obstructive sleep apnea tonsils, Peritonsillar abscess management, Friedman tonsil grading, Tonsillectomy viva questions, ENT practical exam, Cold steel tonsillectomy, Secondary hemorrhage tonsillectomy, Tonsillectomy patient care, CBME curriculum ENT, Otolaryngology surgery notes, Tonsillotomy vs tonsillectomy, Hot tonsillectomy, Dexamethasone tonsillectomy, Reye’s syndrome aspirin tonsillectomy